Introduction: Loading Hope on Tape

In the late 1980s, while British kids were swapping pirated copies of Chuckie Egg and bickering over whether the C64 or Spectrum had better gameplay, children in Czechoslovakia were quietly assembling their own microcomputers. Not metaphorically — actually soldering the boards. You see, behind the Iron Curtain, technology was as much about resourcefulness as it was about circuitry.

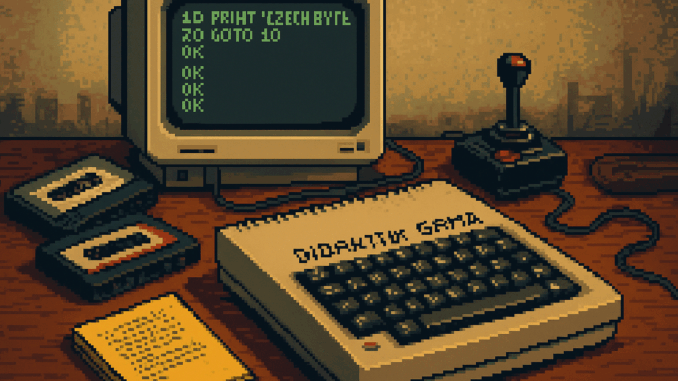

Picture a dimly lit bedroom in Brno, 1987. A teenage boy sits cross-legged on a threadbare rug, waiting for a copied cassette to load on his Didaktik Gama. The hiss of the tape fills the room, joined by the clatter of radiators and the faint murmur of a state news broadcast next door. This anecdote comes from a Bytefest interview I attended in 2023 — the boy is now a university professor in Brno, but he still has the same Gama on his desk.

Where we had Dixons, Ceefax game tips, and cover-mounted cassettes from Your Sinclair, Czech enthusiasts had rationed silicon, Soviet restrictions, and a hunger to create. Yet somehow, despite the odds, an entire retrocomputing culture thrived — underground, unpolished, and utterly brilliant. This is the story of how 8-bit survived in Czechoslovakia, and how its legacy still pulses through Czech tech today.

Historical Context: State Machines and Silicon Sanctions

During the Cold War, Czechoslovakia found itself on the receiving end of the CoCom embargo — a Western-led restriction on exporting high-tech goods to the Eastern Bloc. Western microcomputers like the BBC Micro, Amstrad CPC, or Apple II were virtually inaccessible. But where politics closed doors, ingenuity opened toolboxes.

The PMD 85, designed by the Tesla electronics company, became a state-sanctioned computer for schools. Clunky, monochrome, and blessed with a BASIC interpreter, it was a triumph of necessity. Around the same time, the IQ 151 — possibly the ugliest computer ever built — served as another domestic attempt at microcomputing. Slow, crash-prone, and prone to overheating, it still introduced a generation to programming.

Then came the Didaktik series — particularly the Didaktik M and Gama — unlicensed clones of the ZX Spectrum that quietly flooded Czech classrooms and living rooms. These machines ran Spectrum software with minor tweaks and formed the backbone of a distinctly local retro scene. They weren’t just running Spectrum games. They were doing it without permission — and somehow, that made it sweeter.

Meanwhile, the Atari 800XE, more readily available in Czechoslovakia than in parts of the West due to late-era trade arrangements with East Germany, became a cult favourite. Its wider availability contributed to the country’s blossoming demoscene and hobbyist culture.

While Western kids were arguing over joystick compatibility, Czech kids were taping copied cassettes under their jackets, trading BASIC games in schoolyards, and squeezing every byte from 48K of RAM.

Modern Implications: From Demoscene to Indie Dreamscapes

With the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989, a generation of hackers, coders, and tinkerers were suddenly unleashed. And they didn’t stop.

Czechia became a hotbed for digital creativity in the 90s and 2000s. Groups like Broncs and Digital Dynamite lit up the demoscene, pushing machines like the ZX Spectrum and Atari 800XE beyond their limits. Broncs’ Madness demo melted minds at Forever 8-bit in 2003 (searchable online), proof that even decades-old hardware still had surprises to offer.

This DIY mindset never vanished. Studios like Amanita Design (Machinarium, Samorost) and Bohemia Interactive (Arma, DayZ) trace their lineage to the era of smuggled cassettes and dodgy RAM expansions. These creators didn’t just learn code — they lived through the scarcity that shaped their entire digital worldview.

Retro computing clubs in Brno and Prague still buzz with activity, restoring Didaktiks, showcasing homemade cartridges, and running 8-bit game jams. While Britain has Bletchley Park and Cambridge nostalgia, Czechia’s preservation efforts are grassroots — built from basements, not brochures.

Future Outlook: Preservation Behind the Pixels

With a growing international interest in Eastern Bloc computing, Czechia is now emerging as a key player in the retro tech preservation movement. Events like Bytefest and RetroGames Expo bring together old-school enthusiasts, hardware restorers, and demoscene veterans — keeping memory chips alive one solder joint at a time.

The challenge now is documentation. While machines like the ZX Spectrum have been exhaustively chronicled in the West, Czech hardware is still woefully underrepresented online. Communities are working to scan manuals, translate interviews, and archive software dumps before this digital folklore is lost.

There’s even talk of creating a national computing museum in Brno — not a polished, interactive playground, but a working, noisy, blinking shrine to Czechoslovakia’s strange and beautiful machines.

Conclusion: Czech Yourself Before You Forget

For a country long denied access to mainstream computing, Czechia made its own future out of spare parts and stubborn joy. The legacy of its 8-bit past isn’t just found in code — it’s in the spirit of reinvention that carries on in indie games, hacker spaces, and blinking LEDs soldered in someone’s kitchen.

Czech retro tech didn’t survive despite its circumstances. It survived because of them. And in that, there’s a lesson for all of us.

Tape up, power on, and never underestimate a kid with a screwdriver and a dream.

Leave a Reply