By Tom “FrameRate” Davies and Nathan Clarke

Introduction: The Day the Frame Rate Changed

Nathan:

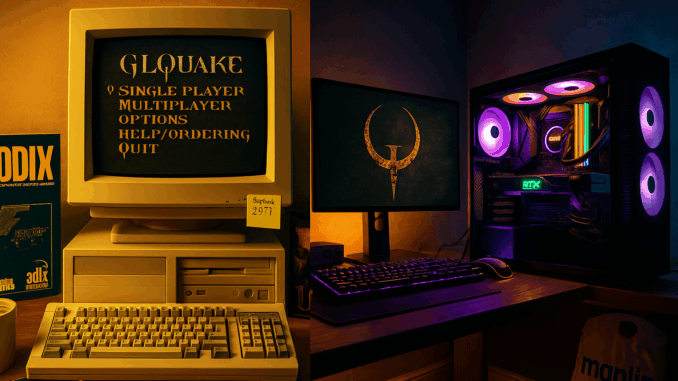

I remember standing in Tempo in Croydon in late 1997, watching the demo PC looping Quake. Next to me, a teenager nudged his dad and said, “Look, it’s not juddery!” What he was actually seeing was the birth of a British gaming fixation, the frame rate obsession. For most of us, games had always been a compromise. Doom and Duke Nukem 3D on a 486 meant pixel soup and choppy scrolling. The arrival of the 3dfx Voodoo Graphics card changed that almost overnight. Suddenly, games like Quake, running on a Voodoo-equipped system, could hit 30 FPS or more at 640×480 with smooth, flicker-free visuals. It was a world away from the choppy, pixelated experience we had tolerated on a 486.

Product Archaeology: Inside the 3dfx Revolution

Tom:

I still have the box from my original Voodoo Graphics, picked up from Computer World in Birmingham. That was back when you could still see rows of shrink-wrapped big box PC games and hardware behind glass. My setup was a beige tower with a Pentium 166MMX and a battered S3 Trio64 for 2D. Installing the Voodoo meant opening the case, slotting in a PCI card, and running a little VGA pass-through cable. You had to keep your 2D card, because Voodoo only did 3D, but what it did, it did perfectly.

Nathan:

The Voodoo Graphics, SST1, ran at 50 MHz and used 4 to 6 MB of EDO RAM, with at least 2 MB allocated as a frame buffer and 2 to 4 MB for textures. Cards with 6 MB could handle larger textures, but were still capped at 640×480 in 16-bit colour. It used Glide, a proprietary API that made developers’ jobs easier, but it locked games into the 3dfx ecosystem. That was a risk, but in 1997, Glide was faster and smoother than Direct3D or OpenGL could manage. If you played Tomb Raider or MechWarrior 2 after fitting a Voodoo, you saw a jump in colour, lighting, and animation that was impossible before.

Historical Evolution: The Rise and Fall of Glide

Nathan:

In the UK, the arrival of Voodoo cards matched the explosion of LAN gaming and benchmarking culture. Suddenly, it was not just about playing the game. It was about how well your machine ran it. Forums like Overclockers UK and PC Zone’s letters page filled with arguments over frame rates and 3DMark scores. I remember spending Saturday mornings at Maplin, comparing notes on which drivers squeezed out the last few frames per second. The frame rate obsession was here to stay.

Tom:

Quake was my personal measuring stick. On my old system:

- Software mode, 320×240: 18 FPS, blurry, jittery

- Voodoo plus Glide, 640×480: 30 to 35 FPS, sharp, smooth, a massive leap from software rendering

- Today, using dgVoodoo2: 160 FPS at 1080p, but you lose some of the CRT magic

Once you had tasted that fluidity, you started chasing it everywhere. AUTOEXEC.BAT and CONFIG.SYS became sacred texts for the UK PC crowd. Voodoo made performance visible and every upgrade was a quest for a higher number.

Nathan:

Glide’s golden age was 1996 to 1998, before Direct3D and OpenGL caught up, and before Nvidia’s aggressive competition overshadowed 3dfx’s proprietary approach. When 3dfx bought STB Systems and tried to manufacture its own cards, they alienated former partners. While Voodoo Rush and Banshee were steps toward all-in-one 2D and 3D cards, neither matched the pure 3D impact of the original Voodoo Graphics or Voodoo 2. By 1999, NVIDIA’s RIVA TNT and GeForce 256 took the crown. The Voodoo 5 arrived late, but was 3dfx’s first card to support full 32-bit colour. It still lacked dedicated hardware transform and lighting, which the competition had by then. In December 2000, NVIDIA acquired 3dfx’s assets. The Glide era ended, but the culture had changed permanently.

Present-Day Investigation: Why Frame Rate Obsession Still Matters

Tom:

It is easy to run nGlide or dgVoodoo2 now and play Glide-era games on modern RTX cards. DOSBox SVN even supports Glide. If you are a real purist, MiSTer FPGA cores now replicate Voodoo graphics almost exactly. I ran Unreal Gold on both my Voodoo 3 AGP build and a modern PC. The new setup smashes the old frame rate, but the real hardware has a unique smoothness and tactile feel. On forums like VOGONS, collectors still debate original cards compared to wrappers or FPGAs. Prices for working Voodoo cards on eBay keep climbing. That proves the frame rate obsession never really died.

Nathan:

Walk into any UK retro event and you will see original Voodoo builds proudly running Quake, Unreal, or Carmageddon. The hardware’s value is not just nostalgia, but a reminder. Smooth gameplay, not just graphics, is what made these machines special. That expectation, smoothness as a standard, originated with 3dfx.

Conclusion: A British Standard for Smoothness

Nathan:

The real legacy of 3dfx is that it made frame rate a badge of pride. Before Voodoo, we settled for whatever the hardware could muster. After Voodoo, smooth gameplay became the baseline. Even with today’s 360Hz OLED monitors, DLSS 3, and NVIDIA Reflex, the UK’s frame rate obsession remains. Those of us who saw Quake leap to 35 FPS on a Voodoo never looked back.

Tom:

And those of us who lived through it? We’re still chasing those frames. We probably always will.

What was your first taste of real smoothness?

Leave a Reply