Introduction

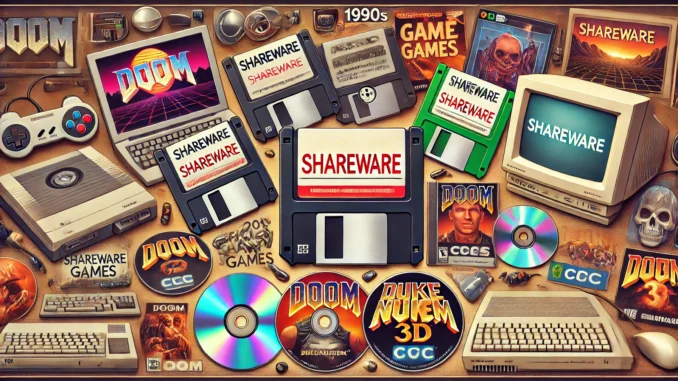

Before Steam and digital downloads, before even CDs, there was shareware. If you grew up in the ’90s, you might remember the thrill of finding a floppy disk packed with new games inside a magazine or downloading a free demo from a dial-up BBS. It revolutionized how software was distributed and discovered. Many players first encountered it through floppy disks included in magazines like PC Gamer and Computer Gaming World, or passed between friends, an exciting way to discover new software for free. Early examples like PC-Talk, a communications program, and PKZIP, a file compression tool, showcased how software could be distributed freely while encouraging voluntary payments. While often associated with gaming, early shareware also played a crucial role in distributing utility software and productivity tools. And it changed everything.

The concept of shareware dates back to the late 1970s and early 1980s, primarily used for utility software and productivity tools. The term “shareware” was first coined by Bob Wallace in 1982, describing software that could be freely shared and tried before an optional purchase. Early shareware programs included text editors, disk utilities, and business applications, distributed through floppy disks and user groups.

The shareware model allowed developers to distribute a portion of their game for free—usually the first episode—enticing players to purchase the full version. This approach revolutionized PC gaming, enabling independent developers to bypass traditional publishing channels and reach audiences directly. Shareware influenced modern digital distribution platforms like Steam, free-to-play models, and mobile gaming. For example, Steam’s early demo-driven approach echoed shareware’s strategy of offering limited content upfront to entice purchases. Games like Left 4 Dead and Portal benefited from this model, using free demos to drive full-game sales.

Among the most iconic shareware successes were Doom (1993) and Duke Nukem 3D (1996). These games not only popularized the model but also set new standards for first-person shooters. This article explores the rise of shareware, its impact on gaming culture, and the reasons for its decline.

The Rise of Shareware Gaming

Origins of Gaming Shareware

By the late ’80s and early ’90s, software piracy was rampant, with cracked retail games widely distributed through bulletin board systems (BBS), floppy disk trading, and early online file-sharing networks. With retail games frequently being copied and cracked, developers needed a way to embrace free distribution while still profiting. According to estimates from the early ’90s, as much as 80% of software used in some regions was pirated, forcing developers to find new business models. Shareware became a natural solution, offering a legitimate means of distributing software widely while encouraging users to purchase the full version.

While shareware existed before, Apogee Software (later 3D Realms) pioneered the episodic shareware model in gaming, where players received the first portion of a game for free and paid for additional episodes. This approach incentivized gamers to pay for the full experience while ensuring developers retained control over their product. The success of this model led to its adoption by id Software and other studios, shaping the future of digital game distribution.

Why Shareware Worked for Gaming

Shareware was revolutionary because it differed from the traditional retail model:

- Try before you buy – Players could sample a game before committing to a purchase, unlike expensive retail titles that offered no refunds.

- Bypassing publishers – Independent developers could distribute their games directly, avoiding store shelves and high distribution costs.

- Grassroots marketing – Shareware relied on word-of-mouth, floppy disk copying, magazine cover disks, and Bulletin Board Systems (BBS) to reach players.

The Role of Floppy Disks and Early Internet

Shareware games were primarily distributed via:

- Floppy disks shared among friends or bundled with PC gaming magazines.

- FTP sites and BBS networks, where early adopters could download and share game files.

- Early internet communities, where fans spread shareware titles far and wide, often modifying and re-uploading them.

Doom and Duke Nukem 3D: Shareware’s Biggest Hits

Doom (id Software, 1993)

Few games exemplify the success of shareware better than Doom. Released as shareware with Episode 1 (Knee-Deep in the Dead) free to download and distribute, Doom became one of the most widely played PC games of all time.

Key factors in Doom‘s success:

- Groundbreaking FPS mechanics – Fluid movement, fast-paced shooting, and intense action.

- Modding capabilities – Allowed players to create custom maps and mods, fueling longevity.

- LAN multiplayer – Doom was one of the first games to popularize local network multiplayer battles.

- Widespread distribution and piracy – Doom was so widely shared that even those who never officially purchased it played it extensively.

Duke Nukem 3D (3D Realms, 1996)

Following in Doom‘s footsteps, Duke Nukem 3D leveraged shareware to build its player base before releasing the full game.

Key elements of Duke Nukem 3D’s success:

- Interactive environments – Players could interact with objects, adding depth to gameplay.

- Humor and personality – The protagonist’s one-liners and action-movie style made it stand out.

- Marketing innovation – The shareware version acted as a free advertisement, leading to high conversion rates for full-game purchases.

Both Doom and Duke Nukem 3D proved that shareware could be a dominant force in game marketing and sales. Their success not only demonstrated the viability of the model but also influenced later indie game distribution, paving the way for self-publishing platforms like Itch.io and even aspects of Steam Greenlight. Their success directly influenced later digital distribution models, including Steam’s early focus on episodic and demo-driven marketing. Games like Half-Life 2: Episode One followed a similar model, releasing smaller portions of a game instead of full-price standalone titles. However, unlike shareware, episodic gaming typically required an upfront commitment rather than a try-before-you-buy approach.

The Cultural and Industry Impact of Shareware

Democratizing PC Gaming

Shareware made high-quality games accessible to anyone with a PC, particularly benefiting students, hobbyist programmers, and those without access to expensive retail software. Since the first episode was free, players could enjoy cutting-edge experiences regardless of budget.

Boosting Indie Development

The model empowered small studios, proving that independent developers could achieve massive success without the backing of major publishers. Companies like id Software, Apogee, and 3D Realms became industry leaders thanks to shareware.

The Evolution of Game Distribution

The principles behind shareware paved the way for:

- Game demos

- Early access releases

- Free-to-play models

- Direct-to-consumer digital stores like Steam, GOG, and Itch.io

Why Shareware Faded Away

CD-ROMs and Retail Sales Took Over

As game sizes increased, floppy disk-based shareware became impractical. CD-ROMs allowed developers to offer full games with far more content, reducing reliance on episodic shareware.

Rise of the Internet and Digital Stores

With platforms like Steam, players could now buy and download full games directly, eliminating the need for shareware-style episodic releases. Interestingly, modern free-to-play models borrow elements of shareware, offering limited content for free with monetization options for full access or premium features. Early platforms like Direct2Drive and Xbox Live Arcade also played a role in transitioning away from physical distribution.

Changing Business Models

The gaming industry shifted towards:

- Full-game purchases, driven by large publishers who favored higher upfront sales over the lower conversion rates of shareware.

- Expansion packs

- Subscription services and online storefronts

- Freemium and free-to-play models, which became the modern equivalent of shareware.

Piracy’s Role in Shareware’s Decline

Although shareware embraced free distribution, it also suffered from piracy:

- Many players never upgraded to the paid versions, hurting developers’ profits.

- By the late ’90s, warez groups and file-sharing services made full cracked versions of games easily accessible.

- Developers responded by shifting to CD key protections and Digital Rights Management (DRM), marking the end of the shareware era.

Conclusion

Without shareware, we might never have had Doom, Duke Nukem, or even the concept of trying a game before you buy it. Could a modern revival of shareware-like models—perhaps through blockchain-based ownership or decentralized distribution—benefit today’s gaming industry? While platforms like Ultra and Gala Games explore blockchain-based distribution, they face challenges similar to early shareware, such as monetization and piracy concerns. The lack of standardized pricing and consumer hesitation over digital ownership mirrors the early struggles of shareware developers seeking sustainable revenue. Some modern indie developers, like Toby Fox with Deltarune and FYQD-Studio with Bright Memory, have experimented with shareware-like releases, offering partial content for free and monetizing expanded versions. Some modern indie developers, such as those on platforms like Itch.io, have experimented with voluntary payment models reminiscent of early shareware. A notable example is Celeste Classic, which was initially released as a free prototype before evolving into a commercial success. Similarly, Deltarune offered its first chapter for free, allowing players to try before committing to future paid installments. Today, elements of shareware persist in gaming, from in-game trials to episodic storytelling and free-to-play mechanics. The model shaped modern gaming, influencing digital distribution, indie development, and marketing strategies. Shareware also helped cultivate early online gaming communities, where players exchanged mods, shared experiences, and spread word-of-mouth recommendations. This grassroots engagement laid the foundation for modern gaming spaces like Discord and Reddit, where indie developers now build fanbases in much the same way.

Lessons for Modern Developers

- The “hook then sell” model still works—seen in free-to-play, demos, and subscriptions.

- Shareware pioneered direct-to-player marketing, a strategy still relevant today.

What do you think? Did you grow up playing shareware games? Which ones were your favorites?

Leave a Reply