Saturday morning, mid-1990s: a greasy spoon’s aroma drifting from next door, my shoes sticky on the newsagent carpet, rain turning to sleet on the glass. The counter boy barely glances up as I reach for the latest issue of Micro Mart magazine, thick as a doorstep, fresh with the smell of proper ink and the faintest whiff of newsstand plastic. If you were lucky, you’d get there before the bloke who always nabbed the best deals in our town. Still shivering from the walk, I’d trudge home, Micro Mart under one arm, tea cooling beside the CRT in my study. The glow of my PC flickered on, promising a Saturday afternoon spent trawling classifieds and plotting impossible upgrades on a shoestring.

For many of us, Micro Mart magazine was not just ink and paper. It was ritual, possibility, and above all, hope in the shape of a half-torn classified ad. The anticipation of that first thumb-through, could there be a cheap SIMM upgrade for my 486 this week? Maybe a “tested” power supply, or a battered Amiga 500 for parts? There was a sense in those pages: the hunt was real, deals were waiting, and the only algorithm guiding your journey was your own impatience.

The Marketplace of Possibility: Micro Mart Magazine’s Classified Culture

Micro Mart magazine was the closest Britain ever got to a true technology bazaar. It was democratic in a way no digital platform has ever truly matched. Every Thursday (for the purists; Saturday for the rest of us) brought a new roll of the dice. Students, hobbyists, repair shops, and eccentrics huddled together on the pages, hawking everything from Dragon 32s with “no PSU but works, probably” to “job lot” RAM whose provenance was anyone’s guess.

Hardware limitations forced developers, and users like us, to treat every resource as precious. I recall haggling by landline for a 1MB SIMM for less than £200, terrified I’d lose the deal if the phone bill got paid late that month. Tech was expensive, and every purchase meant a real sacrifice. You learnt the value of a byte in those days, because wasted memory was often a week’s worth of lunches.

The Micro Mart classifieds were anarchic, uncurated, and gloriously unpredictable. Chance discoveries kept you coming back. There was the time I found a barely-used SCSI controller “priced to shift,” two streets away, or snagged a VIDC-enhanced Acorn monitor for my Archimedes after a tip-off from a stranger in the repairs section. Readers’ Dives offered wild stories and odd bargains. The magazine had room for everyone: the bodger with a bin bag of floppy drives, the would-be entrepreneur flipping chips, and even the chap who only ever seemed to be looking for “Amiga joysticks, cash waiting.”

Beyond transactions, Micro Mart magazine was conversation. The magazine’s forums and reader letters became a lifeblood for a still-young British computing scene. I cut my teeth swapping advice with blokes scraping together second-hand 286s for their kids, or fielding “friendly debates” on why the BBC Micro outclassed anything by Amstrad. Rivalries, Amiga versus PC, Mac versus, well, everyone, flared up in the back pages and in the legendary chatrooms.

The editorial team, with their quirky humour and “Tales from the Towers,” fostered both loyalty and a sense of belonging. You remember the static shocks from swapping cables, but also the static charge when your letter got printed. The unsung editors who fielded hundreds of reader letters each week, and the regular contributors who kept the advice columns lively, deserve more credit than they ever received.

Careers, friendships, and more than a few lifelong rivalries were born in those columns. I met a long-standing collaborator through the classified ads, each of us chasing batches of untested RAM and pooling our three-pin plug spares. That sense of community was real and messy. Every so often someone would blow their last fuse, literally or figuratively, and find a gentle word, or gentle ribbing, in the advice columns.

It was also a haven for overlooked systems. The Oric-1 and Tatung Einstein, for example, found their last champions in those pages, with classified ads and technical queries that kept their tiny communities alive long after mainstream shops had moved on.

The Human Cost: Every Byte Was Earned

Those old issues of Micro Mart magazine reflect realities modern tech buyers rarely see. £50 for a twenty-megabyte hard drive felt outrageous, but it was the cheapest ticket to stay competitive. I missed lunch for a month to afford my first AdLib card, then wired up the wrong ISA pins and watched it spark. Only a fellow Mart reader posted me a replacement at cost.

You remember the agony of waiting for kits posted “payment on receipt,” and the adrenaline rush when a package finally arrived, battered but containing untold potential. Tech dreams were always balanced by hard decisions. Choices mattered. There was no next-day delivery or buy-now-pay-later. There was strategy: Shall I risk “untested, probably works” for a tenner off, or play it safe? Shall I swap two boxes of knackered Sinclair power bricks for a maybe-working RAM stick?

Shrewd readers could upgrade incrementally, trading up through classifieds as cash and opportunity allowed. That classified section acted as great equaliser. The struggling student might luck into an Amstrad at mates’ rates, while the part-time trader found enough bargains to turn a profit.

There were disasters. I once bought a set of “tested” Amiga floppies that corrupted everything they touched. But the thrill of the hunt made every setback worthwhile.

What We’ve Lost: From Micro Mart Magazine’s Bazaar to Today’s Algorithms

Today’s digital marketplaces offer convenience and sterile efficiency, but the serendipity is gone. When I visit modern e-commerce platforms, it’s difficult not to mourn the end of chaotic possibility. We traded chance encounters for algorithms. There is no more scanning for local sellers with a sense of humour or one-off oddities buried beneath layers of careful curation.

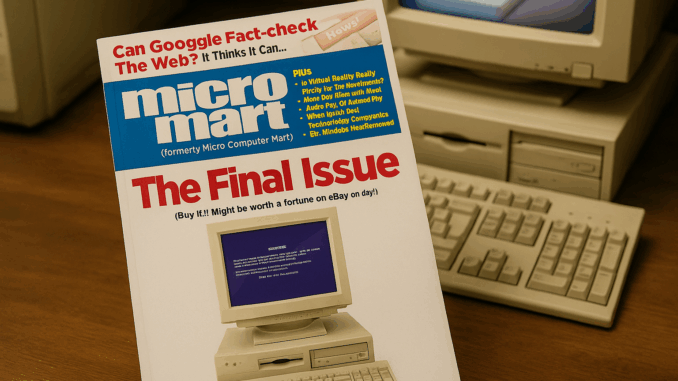

Micro Mart magazine’s closure didn’t just signal the end of print. It marked the dissolution of a broad, welcoming community. Deals were once brokered on trust and the familiar ring of the home phone, relationships built by reputation rather than ratings. There were handshake deals, missed connections, and the occasional con, always tempered by the collective wisdom of the advice pages and the relentless peer review of the chatrooms.

The decline of this bazaar mindset has cost us more than convenience. A generation learned its trade through trial, error, and late-night conversations. You remember chasing the postman after school or mailing payment with a classified listing, every penny counted.

What we’ve lost, as the classifieds fractured into Reddit forums, Discord servers, and eBay “Buy It Now”s, is the tangible culture: the ritual of the hunt, the camaraderie in disaster, and a shared record of British computing history. Micro Mart magazine chronicled real evolution, from the ZX81’s reign to the rise of the Pentium, from blue screens to broadband. In our current algorithmic order, that communal texture is gone. There are still bargains, but few stories and even fewer connections that last beyond the next click.

The historical thread is clear. The magazine’s forums and chatrooms were the direct ancestors of today’s Discord servers, Reddit communities, and specialist Facebook groups. The difference is in the texture: Micro Mart magazine’s culture was built on open participation, unpredictable encounters, and a sense of shared adventure. Modern platforms offer reach and speed, but rarely the same sense of belonging or the thrill of the unexpected.

Why Micro Mart Magazine Still Matters

For those of us who lived through it, Micro Mart magazine symbolises an era when technology was personal, tactile, and gloriously unpredictable. The best discoveries weren’t recommended by algorithms. They were found by persistence, conversation, and sometimes sheer luck.

For the new generation discovering retro tech, the magazine’s ethos is a reminder: don’t wait for suggestions, dig for yourself, and celebrate the beauty of the uncurated.

The spirit of Micro Mart magazine lives on in every community-driven preservation project and every weekend spent coaxing a floppy drive back to life. The ethos, open, participatory, rooted in lived experience, is a blueprint for digital preservation today. We keep these systems alive not out of nostalgia, but because every rescued machine and revived story matters. Community archives, homebrew fairs, even social media swaps can learn from the inclusivity, messiness, and genuine adventure that Micro Mart magazine fostered.

Its magic lay in its openness. Anyone could contribute, anyone could win or lose, and every week brought something nobody could have predicted. It was never meant to be perfect. The thrill and the risk were inseparable.

Keeping the Adventure Alive

Sometimes I still find myself flipping through old issues, the pages curled and newsprint yellowed, half-expecting to find next week’s upgrade waiting. In my London study, the CRTs still flicker and the soldering iron sits ready, but the real legacy of Micro Mart magazine is the community it stitched together from rain-soaked newsagents to phone-blistered hands.

If you’re reading this, pining for that old thrill, you’re not alone. The world may have moved on, but there’s still room for a bit of unpredictability, a bit of earned victory. Next time you’re at a local retro tech fair, tea provided, static shocks not guaranteed, say hello and swap a story. The web was never meant to be polished. It was meant to be an adventure.

What was your first Micro Mart magazine bargain or disaster? Share your stories, keep seeking, keep fixing, and never lose that love for the uncurated. Micro Mart magazine was never just a magazine. It was, and still is, a testament to the messy, marvellous community that made British computing history worth saving.

Read more about Micro Mart magazine on Wikipedia.

Curious for more stories from the bench? Find my other articles at https://netscapenation.co.uk/author/Nathan/

Leave a Reply