The Shed, the Storm, and a Sudden Idea

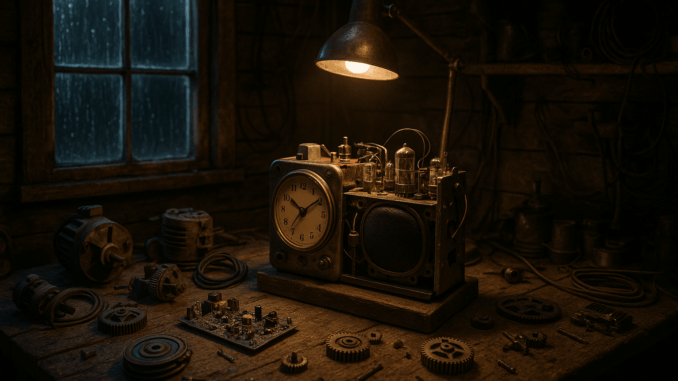

Cold tea. That detail is what lingers from countless nights on the bench, and it’s how I remember the first time I paid real notice to the invention that would become the clockwork radio. If you were to step into Trevor Baylis’s shed on Eel Pie Island that autumn evening in 1991, you might have noticed clutter everywhere: jars of split screws, salvaged transistor boards, the faint tang of solder in the air. Through the rain-brushed window, the Thames widened beneath lowering clouds. Inside, Trevor watched a BBC documentary on the African AIDS crisis.

Radio, they said, was the single most reliable link for remote communities, yet batteries were a luxury. You can almost picture him setting his mug down mid-spill, disappearing to the workbench and sweeping aside yesterday’s project for a wind-up music box, a battered toy car motor, and a plastic-cased radio. This wasn’t the stuff of Silicon Valley whiteboards or venture capital brainstorms. Thirty minutes later, the world had a gadget that, once wound, would play for a precious handful of minutes, powered not by copper-topped cells but by hope and persistence. I know, because I’ve built and bodged plenty of similar contraptions myself. Nothing compares to the surprise of an “it actually works” moment, especially in the dim wash of a CRT or by the light of an old table lamp.

Baylis’s spark was pure British bench ingenuity. It was the same kind of lateral thinking that underpinned the homebrew computer days: making do, making it better, and making sure it did a bit more than anyone expected.

A Life Measured in Improvisations

If Trevor Baylis had stopped at that first prototype, we’d still have cause to cheer. But his story, and the story of the clockwork radio, runs far deeper. He was born in 1937, an athletic child with a touch of the performer. He could have become an Olympian, but a missed spot on the team diverted him to what he called “banana skin luck.” His career read like something you’d get from spinning the dials on the old radio itself: Army instructor, circus stuntman, underwater escape artist for the Berlin Circus, professional showman. Stories like his were why magazine columns thrived back when 640K was enough for everyone and you could still get a static shock off your Amstrad’s case.

Baylis’s real passion wasn’t applause but helping people who’d been knocked askew by life’s random chaos. “Disability is only a banana skin away,” he liked to say. After seeing stunt friends laid low by injuries, he designed over two hundred simple aids, everything from single-handed tin openers to sketching easels for those who’d lost their grip. It was all fuel for a mindset that believed gadgets should offer a second chance.

Clockwork Magic Unpacked: How the Radio Beat the Battery

So, what made the clockwork radio special? Let’s look under the plastic, as any proper tinkerer would. At the heart was a coiled carbon-steel spring, textured for maximum tension, wound by the user’s hand. Thirty seconds of winding stored enough energy to drive the internals for half an hour. Later models stretched that to nearly an hour. The mechanical energy passed through a reduction gearbox, steadily unwinding to turn a Mabuchi RF-500TB DC motor used here as a generator. That generator output about 35mA at 3V, just enough for the low-draw transistor radio circuit inside. You could almost feel the satisfaction as each tooth of the gear meshed. No arcing, no magic smoke, just pure mechanical-to-electrical conversion humming away.

The build? Sturdy ABS casing, five pounds if you dropped it on your toe, heavier than any cheap supermarket radio but every millimetre engineered for repairability and decades of rough handling. They used nearly 150 components, but most could be recycled, replaced, or jury-rigged if something went wrong. It’s a far cry from today’s “warranty void if seal broken” nonsense. I still have more success fixing kit from the BayGen era than today’s disposable efforts.

This cleverness ran from the micro right up to the macro. The four-inch speaker was nothing to look at, but properly mounted it could fill a room. The radio’s output didn’t just relay news but voice, music, and, most crucial of all, community.

Beyond the Shed: A Tool for Survival

It’s easy to romanticise the inventor. Reality, as Baylis discovered, was more fraught. Major firms, Philips, Marconi, even Virgin, turned him down flat. Someone in Glasgow barely hid their laughter when he arrived for a meeting. The Design Council rejected his idea outright. “The feeling of rejection, we’re in committee, says that what you’ve done is no good, it hurts, you know,” Baylis recalled. Only after a feature on BBC’s “Tomorrow’s World” in 1994 did the story shift. Suddenly, his shed-built radio caught fire. Business partners stepped in, forming BayGen Power Industries and building a factory in Cape Town. There, disabled workers and ex-offenders assembled radios to send into the world, a decision as practical as it was ethical, giving new meaning to “design for good”.

Nelson Mandela himself supported the clockwork radio. Imagine the world’s most famous political prisoner, now President, recognising the power of a device you can hold and wind in your palm, that can reach the reaches no grid can touch. NGOs from Save the Children to Medecins Sans Frontieres distributed hundreds of thousands of sets. One radio could bring health advice, educational programming, political news, lifelines not luxuries to villages otherwise cut off by geography and poverty. Over a million radios were distributed, ultimately benefiting more than six million people and changing the pattern of disaster response across forty countries. And to think, it all began with a hack in a garden shed by the Thames.

Struggles, Sacrifice, and a Bitter Irony

Yet the fairytale had teeth. As production scaled, cold economics intruded. Manufacturing costs in South Africa outpaced the revenue, so in 2000, two-thirds of production moved to China. Jobs vanished, almost half the Cape Town staff, including 29 disabled workers, were lost. Most radios ended up in Western garages or holiday cottages, their green credentials appealing to well-heeled buyers rather than the African villagers who needed them most. The hard truth: humanitarian technology isn’t immune to market pressure.

Worse still, Baylis saw little reward. Patent battles broke out and his rights faded after his original design underwent corporate “improvement.” Later, UK patent authorities even named an additional co-inventor, David Broughton, after a long dispute. Baylis’s own share whittled away. “They took my patent and my profits,” he once said, and by the time the radio was in millions of hands, the man who built it was living on the slender margins of his after-dinner speeches.

It is the cruel heart of the inventor’s dilemma. You bring a world-changing idea into being only to see its rewards washed away by bigger hands, brisker lawyers, or a lack of business wiles. Yet Baylis refused bitterness. He pivoted, founding Trevor Baylis Brands to help other inventors protect their ideas. “Disability is only a banana skin away,” he reminded young entrepreneurs, and he turned his fight for justice into a cause.

The Clockwork Legacy: More Than a Moment

The clockwork radio wasn’t just a product or a footnote. It lit a path for sustainable design, showing tech companies and tinkerers alike that batteries and sockets aren’t the only way to connect, educate, or save. Its DNA is everywhere now: wind-up torches, mobile phone chargers, even those clever “electric shoes” Baylis developed, which stored up the energy of each step to power a radio or charge a mobile on the hoof. I remember the first time I saw such a charger, a technical marvel that drew a direct line back to a shed full of old springs and cogs.

It forced the conversation toward repairability, recycling, and longevity in an era obsessed by the disposable and the new. The clockwork radio would work after being dropped, kicked, or submerged in dust. The same could not be said for most 2025 gadgets. The real enduring power was cultural: what mattered was access, durability, and the humanness of a device anyone could use, fix, and rely on.

Conclusion: Lessons We Still Need

Trevor Baylis did not die a rich man, nor did he ride the golden escalator of Silicon dreams. He died alone, but not unremembered, his funeral marked (fittingly) by a clockwork radio coffin. The story is rarely fair, even when the invention is a miracle of simplicity. But Baylis left something behind which still matters, a reminder that invention is both an act of technical courage and grit.

We all remember the thrill of cobbling together a repair in the dead of night, or simply believe there must be a better way to make technology serve; the story of the clockwork radio stands ready to be wound up and played again.

Let’s keep remembering, repairing, and recording. The web and the world was meant to be an adventure, after all. And sometimes, all it takes to start is the quiet, hopeful turning of a spring.

All you ever need to know about clockwork radio !