Introduction: When “One More Turn” Was Born on Cassette

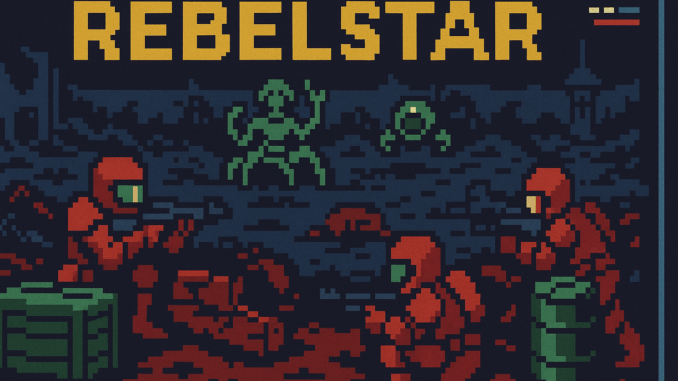

It’s the late 1980s, and you’re clutching a budget game from your local shop-drawn in by mysterious box art and a name that suggests intergalactic rebellion. If, like me, you grew up with an Amstrad CPC 464 humming away on the kitchen table, chances are you’ve got fond (if slightly nerve-shredded) memories of waiting for Rebelstar to load. No cartridge quick-starts here-just the whir and click of a cassette deck, and the promise of a new kind of tactical gaming.

Rebelstar wasn’t a blockbuster. It was a pocket-money purchase, cheap as chips, a Firebird cassette that delivered hours of late-night obsession. For many of us, it wasn’t just a game-it was an introduction to a world where every decision mattered, every squad move had consequence, and tactical depth wasn’t just for chess clubs or tabletop Warhammer fans. Rebelstar was the game that, for a certain generation, made turn-based tactics something you could play in your bedroom, not just in your school Warhammer Club.

In this article, I’ll dig into the story behind Rebelstar’s development, why it mattered, and how it quietly reshaped the DNA of strategy gaming-from the 8-bit era through to the X-COM phenomenon and beyond. Along the way, we’ll look at why the Amstrad and Spectrum led the charge, why Commodore kids missed out, and what made this British title such an enduring classic.

Historical Context: From Tabletop to Tape – The Gollop Blueprint

To appreciate Rebelstar’s legacy, you need to understand Julian Gollop-a British student and tabletop gaming obsessive who decided to drag his hobby into the digital age. His first effort, Rebelstar Raiders (1984), was cobbled together in BASIC for the ZX Spectrum and demanded two human players-no computer opponents, just you and a mate, plotting lunar base shootouts with makeshift tokens and character sheets . Even at this early stage, the bones of something remarkable were there: action points, squad stats, line of sight, and a relentless focus on tactical choice.

The real breakthrough came with Rebelstar (1986). Firebird gave Gollop the keys to their publishing arm, and in return he delivered a machine code version that could support solo play-complete with computer AI, sprawling scrolling maps, and innovations like morale, stamina, and encumbrance. If you were a Warhammer or Dungeons & Dragons fan, it was like seeing your favourite ruleset brought to life on the telly.

What set Rebelstar apart? Not flashy graphics, but depth. Every squad member had individual stats (think: stamina, skill, morale). Each turn, you managed action points-should you run for cover, pop off a risky shot, or pick up a fallen comrade? The “opportunity fire” mechanic meant that, just like real skirmishes, you never felt entirely safe on your turn.

Here’s the bit that mattered for Amstrad and Spectrum kids: while the ZX Spectrum version arrived first in 1986, the Amstrad CPC got its own official port in 1987. Both versions shared the same gameplay magic and budget price tag, making them a rite of passage for British home computing fans. Meanwhile, Commodore 64 users could only read about Rebelstar in the magazines; despite a flurry of adverts, technical and publisher woes meant a C64 version never appeared .

Modern Implications: The Rebelstar Family Tree and Tactical Gaming’s Evolution

Rebelstar didn’t just invent new ways to play-it spawned an entire genre. Gollop took the blueprint he’d forged here and pushed it even further in Laser Squad (1988), a game that introduced destructible environments, tighter AI, and deeper squad management. Laser Squad finally made it to the C64, but by then the centre of gravity had shifted: British microcomputers were the place for turn-based tactics, and everyone from Amstrad and Spectrum owners to future PC strategists took note .

But the real seismic shift was still to come. The lessons learned in Rebelstar’s corridors and moonbases were baked into X-COM: UFO Defense (1994). Gollop’s “one more turn” magic-action points, squad-level anxiety, emergent storytelling-became the template for a new era of global gaming. If you’ve played any modern tactics game (think: XCOM, Jagged Alliance, Into the Breach, or even Final Fantasy Tactics), you owe a debt to those budget cassettes.

Rebelstar’s influence is more than technical-it’s emotional. Ask any Gen-X gamer, and they’ll tell you about late-night marathons, tense last stands, or the heartbreak of losing your best squad member to a lucky shot. It taught us patience, strategy, and the art of living with our choices-a kind of digital chess for the space age.

Future Outlook: Preservation, Rediscovery, and the Enduring British Spirit

So where does Rebelstar fit in today’s fast-forward digital world? If anything, its star burns brighter. Modern developers constantly cite Gollop’s work as a lodestar for tight design and replayability. The resurgence of turn-based tactics in the indie scene (think: Phoenix Point, a spiritual successor by Gollop himself, or the Rebelstar: Tactical Command revival on GBA) proves that the appetite for deep, thoughtful gameplay has never gone away .

There’s also a lesson here about preservation and cultural memory. Rebelstar is a reminder that some of the world’s most influential game design didn’t come from corporate boardrooms-it came from British bedrooms, tape decks, and the imaginations of a generation determined to make their mark. In an era of disposable digital entertainment, the act of remembering, archiving, and replaying games like Rebelstar is an act of cultural stewardship.

Conclusion: The British Budget Game That Changed the Game

Rebelstar might have begun as a budget curiosity-a cool name, flashy cover, and a pocket-money price-but its legacy is anything but small. It’s the proof that British ingenuity, a love of wargaming, and the home computing boom could deliver world-class game design from a humble cassette.

The next time you fire up a modern tactics game, spare a thought for Rebelstar, Julian Gollop, and that nervy wait as your Amstrad or Spectrum chewed through the tape. This wasn’t just the birth of a genre-it was the moment “one more turn” became a mantra, and British gamers took command of the future, one action point at a time.

Leave a Reply