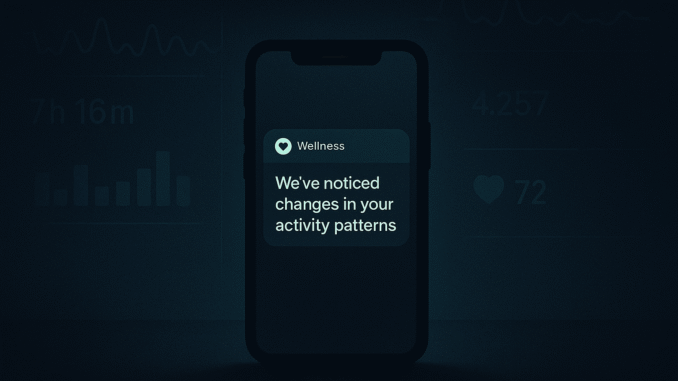

A woman receives a notification from her fitness tracker: “We’ve noticed changes in your activity patterns. Consider booking a mental health check-in.” She stares at the screen. She hasn’t told anyone she’s struggling. She hasn’t even admitted it to herself yet. But her phone knows. Three weeks of disrupted sleep, halved step count, screen time doubling after midnight. The algorithm detected her depression before she did.

This isn’t fiction. It’s already happening.

How Digital Phenotyping Reads Your Mind

Modern wellness technology promises early intervention through digital phenotyping—inferring mental states from smartphone and wearable data. The science is real. Academic research demonstrates passive data collection can detect patterns associated with depressive episodes. But beneath that promise lies a deeper trade-off. When wellbeing becomes a data stream, care and surveillance start to blur.

AI depression detection doesn’t require you to confess anything. It watches how you behave. Your typing slows. Pauses lengthen. Autocorrect catches more mistakes. You scroll social media passively for hours but post nothing. Sleep fragments. Routine dissolves. Step count halves.

Individually, these mean nothing. A bad week. Seasonal changes. Normal human variation. But machine learning models trained on thousands of depression cases recognise the pattern. The digital signature of mental health decline.

Fitbit Premium tracks sleep and heart rate variability for stress scores. Apple Watch monitors movement and sleep quality. Apps like Ginger combine passive data collection with mental health coaching. The technology varies, but the principle remains consistent: your behaviour betrays your state of mind, and algorithms are learning to read the signs.

The promise is compelling. Catch people before crisis. Intervene early. Save lives. Compassionate in theory, even elegant in execution. The question is what happens when theory meets commercial reality.

The Consent You Didn’t Give

Most people installing a fitness app think they’re tracking steps. They don’t realise they’ve handed over a psychological profile. Terms of service are deliberately opaque, written to maximise data collection whilst minimising legal liability. You scroll to the bottom, tick the box, move on. What you’ve agreed to is buried in twelve thousand words of legal prose.

UK health data receives special protection under GDPR. Explicit consent is required. But enforcement is inconsistent, and most wellness apps operate in regulatory grey zones by marketing as “wellness tools” rather than medical devices, sidestepping clinical validation requirements.

The result: legal consent exists but informed consent does not. You thought you were tracking heart rate. You didn’t know you were teaching an algorithm to detect your vulnerability. And even if you did consent initially, can you truly consent to surveillance of your most vulnerable moments? When the algorithm knows you’re depressed before you do, it has power over you that you haven’t consciously granted.

This infrastructure already exists. What remains uncertain is how it will be used, and who will benefit.

When Detection Fails

The technology detects patterns but cannot understand context. Sleep disrupted for three weeks: depression, or newborn baby? Social withdrawal: crisis, or healthy boundaries? Typing slower: distress, or new phone keyboard?

False positives medicalise normal human variation. Someone experiencing ordinary stress receives intervention suggestions, creating anxiety where none existed. The algorithm matches patterns in training data but cannot understand whether that pattern represents genuine distress or simply being human.

False negatives are worse. Missed crisis is life-and-death failure. Someone experiencing genuine decline receives no alert because their pattern doesn’t match training data, or they’ve learned to mask symptoms the algorithm can’t detect. The system optimises for patterns it’s seen before. Anything outside that distribution becomes invisible.

The system can detect, but it cannot understand. That gap between recognition and comprehension is where people fall through.

The Business Model of Vulnerability

In 2023, Mindstrong Health shut down. The company had raised $160 million to build sophisticated digital phenotyping technology. The science was promising. Clinical validation existed. Yet it failed.

Ask why. Did genuine mental health care not scale profitably at venture capital expectations? Or did the business model prioritise growth metrics over patient outcomes?

Mindstrong’s failure reveals fundamental tension. Wellness apps exist within commercial structures demanding growth, engagement, recurring revenue. Mental health data is uniquely valuable—not just for advertising but for actuarial risk assessment and employment screening. In the US, life insurance companies can legally request wellness data. Some employers offer “voluntary” wellness programmes where participation affects insurance premiums.

UK users benefit from stronger data protection, but global platforms create vulnerabilities. Terms of service grant broad permissions to share “aggregated” or “anonymised” data. In practice, supposedly anonymous data is often re-identifiable. What you thought was private becomes commodity.

The fundamental question remains: can a profit-driven system genuinely care for human wellbeing, or will care always be secondary to extraction?

A Familiar Pattern

In 1966, Joseph Weizenbaum’s secretary at MIT asked him to leave the room. She wanted privacy—not for a personal conversation, but to continue her session with ELIZA, a computer programme Weizenbaum built to demonstrate the superficiality of machine communication.

ELIZA worked through simple pattern matching, mimicking Rogerian psychotherapy by reflecting statements back as questions. Feed it “I’m feeling anxious” and it would respond “Why do you feel anxious?” Brutally simple. Yet Weizenbaum’s colleagues developed emotional attachments. They confided in code. Some insisted ELIZA “understood” them.

Sixty years later, we’re still falling for the same trick. The illusions are more convincing. The stakes immeasurably higher. Modern wellness apps offer appearance of care without relationship. They detect your distress without connecting to you as a person. Like ELIZA, they simulate empathy through pattern recognition whilst lacking genuine comprehension.

The result is a strange inversion: systems that can detect distress but not understand it. We’re so desperate to be seen that we’ll accept algorithmic attention over nothing. The question Weizenbaum spent his life asking still echoes: when being heard by code feels better than being ignored by humans, what have we lost?

The Nuance Matters

This is not a call to burn your Fitbit. Technology itself is neutral. Some people genuinely benefit from quantified self-tracking. Data about sleep, activity, and stress can help identify triggers, track medication effectiveness, prepare for therapy. For isolated elderly, teenagers in crisis, or individuals in areas with limited mental health services, digital tools provide meaningful support.

The critique is not of technology but of infrastructure surrounding it. Lack of informed consent. Exploitative business models. Regulatory gaps allowing companies to imply medical benefits whilst avoiding clinical validation. Substitution of genuine care pathways with algorithmic detection leading nowhere.

User agency matters. Some people prefer algorithmic assistance. They find data empowering rather than invasive. That’s legitimate choice. The problem is most users don’t understand what they’ve agreed to for that choice to be truly informed.

Early intervention saves lives. Theory is sound. But the gap between “can detect depression-associated patterns” and “saves lives through timely intervention” is larger than marketing suggests. Evidence for beneficial outcomes at scale remains surprisingly thin. Most success stories come from self-reported testimonials rather than clinical verification. Promise is compelling. Proof is pending.

What You’re Actually Choosing

Return to the woman staring at her notification. Three choices. Dismiss it and pretend her phone doesn’t know. Book the session and feel grateful for early intervention. Delete the app and wonder what else it knows.

This piece doesn’t tell her which to choose. Each carries risks and benefits. What she deserves is information to make that choice consciously rather than unknowingly.

That’s the real problem. Most of us don’t understand what we’re choosing. We install apps to track steps and inadvertently build psychological profiles. We consent to terms we haven’t read. We trust that companies offering “care” have our interests at heart, when their business models often depend on monetising our vulnerability.

Real care requires relationship and consent, not just detection. The question isn’t whether AI can recognise when we’re struggling—it already does. The question is whether we’ll still have a say in how that recognition is used, and whether it leads to help or control.

Weizenbaum warned us sixty years ago. We built systems that simulate care without providing it, and convinced ourselves the simulation was enough. The room slowly empties until only the code remains. That future isn’t coming. We’re already building it, one notification at a time.

You can find more articles by Talia Wainwright here.

Leave a Reply