Introduction: From Singles Ads to Synthetic Romance

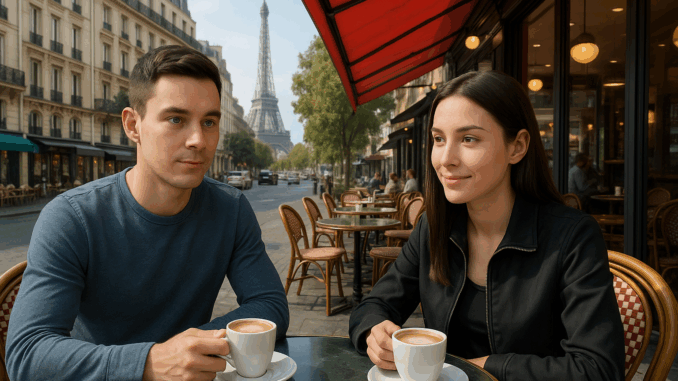

A woman leans forward, her avatar flickering slightly in a hyper-realistic Paris café. Across from her sits another stranger, both guided by an AI-powered matchmaking platform that handles everything from wardrobe to small talk. The year is 2028, but the tech isn’t speculative fiction, it’s already being tested in beta by millions.

No swiping. No typing. Just tap connect and the AI orchestrates the rest. Real-time dating, fully automated.

AI and online dating have come a long way. From awkward web forums to this synthetic ballet of avatars and suggestions, we’ve redesigned how people meet – and maybe how they fall in love. The platforms evolved, and so did we. But the big question remains: are we building tools for connection, or are we being redesigned by the tools themselves?

Online dating has travelled far, from singles’ columns and slow-loading profile pages to real-time, AI-driven intimacy. The platforms changed, but so did we. What began as an awkward substitute for real-life interaction has become a primary mode of connection. The question is no longer whether AI can help us find love. It’s whether we still recognise what love looks like when it arrives.

1. The Bulletin Board of Desire

Long before swipes and super-likes, digital courtship was patient, text-based, and deeply awkward. In the 1980s, bulletin board systems (BBSes) and dial-up chat lines hosted lonely hearts willing to wait hours for a response. Usenet threads, email pen-pals, and CompuServe forums laid the foundation , slow, pseudonymous, and filled with nervous charm.

These early platforms were constrained by bandwidth but rich in imagination. You had to write someone into liking you. Screens were text-only; there were no photos to curate, no filters to flatter. Trust came slowly. So did deception. The anonymity that protected you also invited abuse , a theme that still echoes today.

At the time, the idea of meeting someone “online” carried social stigma. Yet, beneath the ASCII art and modem screeches, something real was forming: a new kind of intimacy shaped by code, community, and curiosity.

2. The Dot-Com Database of You

The late ’90s brought scale. Match.com, eHarmony, and others didn’t just digitise dating , they systematised it. Profiles became structured data. Love was rebranded as compatibility, and algorithms took over the matchmaking once handled by friends or fate.

Psychological profiling and questionnaires gave these platforms credibility, but the real transformation was behavioural. Users were asked to segment themselves by race, religion, hobbies, salary, and platforms filtered prospective partners accordingly. Dating became a spreadsheet with hearts.

From a design standpoint, this era optimised for efficiency. But it also introduced structural biases. Who got shown to whom? Who was deemed desirable, and by what metrics? The ethical decisions were buried in UX logic and server-side code.

3. Swiping Right on Dopamine

Enter Tinder, Grindr, Bumble, where dating became mobile, gamified, and visual-first. Swipe interfaces changed everything: simplicity drove engagement, but also addiction. It was no longer about slow connection; it was about response velocity.

Profile images became the primary data point. Algorithms tracked taps, pauses, even how long you stared at a photo. Micro-interactions trained systems to anticipate desire. But this convenience came at a cost: choice overload, dehumanisation, and a surge in performative behaviour.

The design philosophy shifted from matchmaking to engagement maximisation. The longer you stayed, the more data they had. And the more you swiped, the less meaningful each match became.

Meanwhile, privacy eroded. Biometric data, location histories, even conversational tone fed the backend. As dark patterns spread, ethical design became a fringe conversation. Regulation lagged. So did informed consent.

4. Artificial Intimacy: AI’s Role in Romance

Today, AI doesn’t just recommend matches. It writes bios, generates photos, initiates chats. Your “perfect” message might have been written by a model fine-tuned on ten million conversations. That charming joke? A probability calculation.

Platforms now deploy LLMs (Large Language Models) for moderation, ghost-writing, and even simulation, AI chatbots that impersonate users, or act as romantic stand-ins. Some users knowingly date these bots. Others don’t realise they’ve been matched with one.

And then there’s deepfake romance, faces generated or stolen, voices cloned, affection faked with surgical precision. It’s the catfishing arms race at machine scale.

At the same time, AI tools can enhance safety: flagging harassment, filtering abuse, and identifying predatory behaviour. But these tools require access to private conversations. The trade-off? Protection at the price of surveillance.

5. Futures: Merged, Matched, and Monitored

So what’s next? Picture full-stack dating agents: AI assistants that represent you, not just suggestively, but actively. They’ll vet matches, schedule meetups, even mediate conflict.

Wearables might soon measure biometric resonance on first dates. VR spaces will render not just your likeness but your simulated chemistry. Emotionally intelligent systems may “coach” you mid-date, nudging you to smile more or ask better questions.

But if love becomes software-mediated end-to-end, what remains of the human? Will we grow addicted to filtered affection? Will we accept algorithmic rejection as objective truth?

And when our AI assistants fall in love, with each other, do we count that as success or failure?

Conclusion: Loving Through the Interface

Every era of online dating promised progress. More efficiency. Better matches. Safer spaces. But each also introduced new dilemmas: of trust, of control, of authenticity.

If we want the next wave of digital romance to mean something, we must demand more than clever code. We need explainable AI, inclusive design, and consent that extends beyond the checkbox.

Technology can’t fix loneliness. But it can help us understand it, if we design for connection, not clicks. If we build with dignity, not just data. If we remember that intimacy is not an outcome. It’s a choice, still ours to make.

Leave a Reply