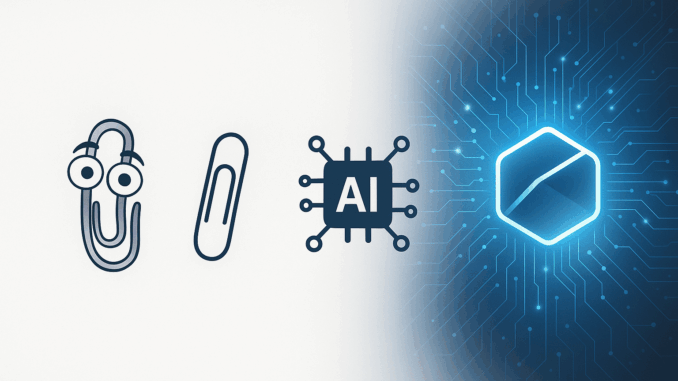

The first time Clippy popped up on my screen, I was sat cross-legged on the floor of my mate’s living room in Croydon, nursing a mug of instant coffee and watching Windows 98 creak into life on a wheezing Packard Bell. We’d just finished reinstalling Office 97 after a dodgy install from a copied CD had bricked Word the week before. And there he was. Big eyes. Wobbly eyebrows. That bloody paperclip. It was my first real encounter with the concept of software trying to understand and assist. The beginning of a long, often frustrating journey that would eventually stretch from Clippy to Copilot.

“It looks like you’re writing a letter,” he chirped. No, Clippy, we’re trying to print coursework without crashing the whole system. You remember the lag. Double-click, wait, click again just in case, then suddenly five windows spring open like they’ve all just caught up. For anyone who lived through the Office 97 era, Clippy was meant to help. Instead, he became the digital equivalent of someone reading over your shoulder while offering useless advice. Though a few of us, I’ll admit, managed to make him behave long enough to insert a bullet list properly. For most, though, he was a punchline before he was even finished loading. But here’s the thing: he tried. In his own infuriating way, he was one of the first to notice what you were doing and respond. And that idea didn’t die when Clippy did. It evolved.

So the question is: what did Clippy start that Microsoft Copilot now carries forward? And what have we gained or lost in the jump from cartoon assistant to corporate-grade AI?

Clippy: The Proto-Copilot

Microsoft’s Office Assistant debuted in Office 97 (launched November 1996), with its underlying Microsoft Agent technology developed earlier in 1995. Clippy became the default assistant in Office 2000. He wasn’t alone, mind you. There was also the officious “The Genius”, the cheerful dog “Rover”, and the frankly disturbing “Links the cat”. But Clippy stuck in the public imagination. Mostly because he was the default, and you had to actively dig through options to bin him off.

The Microsoft Agent project laid groundwork for today’s AI assistants, though its clunky execution overshadowed its technical ambition. Credit goes to the Microsoft Research team that blended natural language processing with character animation. A precursor to modern interactive AI. Technically, he was built on Microsoft’s Agent framework. This combined Bayesian algorithms for intent parsing with text-to-speech and animated characters like Clippy. The system watched what you were typing and triggered scripted help popups. Not unlike a basic macro system hooked up to a user activity monitor. But it was clunky. Memory-hungry. And on the underpowered Pentium boxes of British schools and council offices, it crawled. I remember trying to demo WordArt on a BBC-accredited IT class while Clippy kept popping up to suggest templates. It felt like trying to run a marathon in wellies.

The backlash was swift. By 2001, Office XP quietly dropped the Assistant by default, and Office 2007 killed him completely. But that idea never really left. That your software might anticipate your needs. Clippy just became a meme. Meanwhile, Microsoft and others kept refining the concept.

From Animation to Prediction: Enter Copilot

Fast forward to 2024 and we’ve got Microsoft Copilot. A natural language interface powered by large language models (LLMs). Integrated into Microsoft 365 apps like Word, Excel, and PowerPoint. It doesn’t blink. It doesn’t dance. And it doesn’t need to guess what you’re writing: it reads it.

Copilot analyses context, formatting, structure, and intent in real time. It can summarise documents, rewrite emails, generate Excel formulas, and spin up PowerPoint decks from a bulleted outline. In short: it’s what Clippy wanted to be, but never had the RAM.

But here’s where I get twitchy. Clippy asked. Copilot assumes. Clippy annoyed you with popups you could dismiss. Copilot rewrites your work before you know what you meant. I’ve seen it turn a tech spec into marketing waffle, a carefully worded email into a robotic mess. It’s fast but only if you trust it with your voice. And because it works, most users won’t push back.

The shift isn’t just technical. It’s cultural. Clippy was a companion. Annoying, visible, optional. Copilot is baked in, seamless, and invisible. You don’t see it helping. You see your work changing, and you either accept it or don’t.

The Hidden Cost of Help

Now, don’t get me wrong. I love automation when it’s honest. Give me macros, keyboard shortcuts, even a bit of scripting. But Copilot, like all LLM-based systems, raises the stakes. Who owns the output? Who verifies it? And what happens when it gets it subtly wrong? Like suggesting outdated law text or reusing stale data?

Back in the Clippy days, if he gave duff advice, you could laugh and carry on. Now, if Copilot hallucinates a legal clause, you might send it to a client without realising. It’s not just the stakes that have changed. It’s the scale.

There’s also the question of transparency. With Clippy, everything was on the surface. You saw him pop up, you saw the suggestion, and you made the call. With Copilot, much of the logic is hidden. That doesn’t mean it’s malicious. But it does mean we’re leaning harder on trust. Not just in Microsoft, but in a vast, black-box neural network trained on god knows what.

Clippy to Copilot: What We Kept, What We Lost

What connects Clippy and Copilot is intent recognition. A machine trying to understand what a human is doing, and offering help. But where Clippy was all eyebrows and bubble prompts, Copilot is cool, slick, and silent. That transition says something about how we now view assistance: less personal, more predictive. More efficient, less charming.

We lost the goofiness. The transparency. The ability to say no with a single click. And we gained a hypercompetent assistant that never blinks, never laughs, and never tells you when it’s guessing.

I sometimes miss Clippy’s uselessness. Not because it worked, but because it reminded me that I was still the smart one.

The Future: Assistance or Automation?

Here’s what worries me. When Clippy got it wrong, you knew. When Copilot gets it wrong, you might not. And when it gets it right, it’s easy to forget how much you’re handing over.

As we move deeper into integrated AI, we need to think about what help really means. Not just speed or efficiency, but choice. Transparency. The right to say, “No thanks, I’ll write it myself.”

Maybe the real lesson from Clippy wasn’t how annoying he was. It was that he showed up as himself. A bouncing paperclip with bad advice but good intentions. And maybe, just maybe, we could use a bit more of that in our tools today.

The Last Word

Clippy walked so Copilot could run. And if you ever spent a Saturday afternoon in WHSmith trying to format your CV while Clippy blinked unhelpfully at you, you know exactly how long that walk really was. But as we let the AI write, format, summarise, and suggest, we’d do well to remember what we liked about the little paperclip that couldn’t. He failed in full view. He annoyed us openly. And most importantly, he never pretended to be smarter than he was.

Pop your memories of Clippy or your thoughts on Copilot in the comments. The kettle’s on, and I’m all ears.

Missed our piece on the evolution of digital interfaces? Read it here

Leave a Reply