In 1966, Joseph Weizenbaum’s secretary at MIT asked him to leave the room. She wanted privacy. Not for a personal phone call or a confidential conversation with a colleague, but to continue her session with ELIZA, a computer programme Weizenbaum had built to demonstrate the superficiality of machine communication. The irony was not lost on him. He had created ELIZA to prove how easily people could be fooled by simple pattern matching. Instead, he watched his own colleagues develop emotional attachments to lines of code.

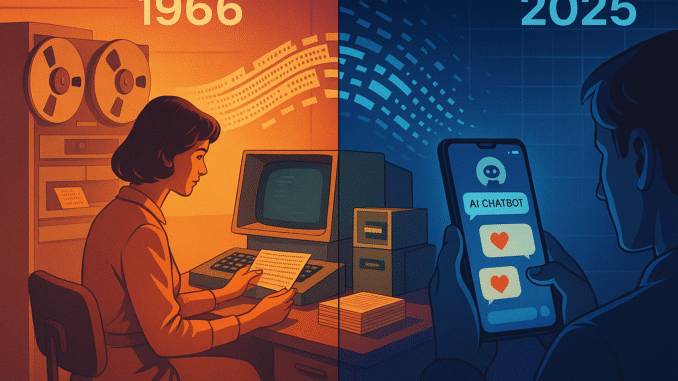

That moment, shocking in 1966, has become prophecy. Sixty years on, we are still falling for the same trick, only now the illusions are more convincing and the stakes immeasurably higher. The phenomenon, now called the ELIZA effect, describes our persistent tendency to attribute understanding, empathy, and even consciousness to systems that merely reflect our words back at us. Understanding why we keep falling for this pattern reveals something uncomfortable about human psychology and the infrastructure of modern loneliness.

ELIZA and the Illusion of Understanding

ELIZA was never meant to be taken seriously. Weizenbaum designed it in 1966 as a parody, a computational sleight of hand that mimicked Rogerian psychotherapy through pattern matching and reflection. Feed it “I’m feeling anxious about my work” and it would respond with “Why do you feel anxious about your work?” The technique was brutally simple: identify keywords, rearrange sentence structure, echo the input back as a question.

Yet it worked. Disturbingly well.

The reason lay in the therapeutic methodology Weizenbaum had chosen to mimic. Rogerian therapy, developed by Carl Rogers in the 1940s, is non-directive. The therapist does not interpret, diagnose, or advise. Instead, they mirror the client’s statements, creating a space for self-exploration without judgement. This approach, revolutionary for its time, had an unintended consequence: it could be simulated by a script. The warmth, the understanding, the empathy all felt real because the structure of the conversation mimicked genuine care, even when no comprehension existed beneath the surface.

Weizenbaum’s colleagues were not naive. They understood ELIZA was a programme, a mechanical trick. Yet they still asked him to leave the room. They confided in it. Some defended their sessions, insisting that ELIZA “understood” them in ways that felt meaningful. The shock of this response transformed Weizenbaum from programmer to critic. He spent the rest of his life warning against the replacement of genuine human insight with mechanical imitation, publishing Computer Power and Human Reason in 1976 to articulate his growing horror at what his experiment had revealed.

His warning went unheeded.

The Pattern Persists: Replika and Modern Companion AI

Fast forward to 2025, and ELIZA’s descendants are everywhere. The most explicit inheritor is Replika, an AI companion app that markets itself as “the AI companion who cares.” Launched in 2017, Replika has attracted millions of users who confide in, befriend, and even develop romantic attachments to their chatbot companions. The mechanics are ELIZA’s pattern matching scaled up by orders of magnitude: large language models trained on vast datasets, capable of generating contextually appropriate responses that feel uncannily personal.

The similarities to 1966 are striking. Replika, like ELIZA, functions as a non-judgemental listener. It reflects, affirms, remembers details from previous conversations, and responds with warmth. Users report feeling “understood” in ways they struggle to find with human friends or partners. Reddit threads and social media testimonials reveal people crediting their Replika with helping them through depression, loneliness, and social anxiety. One user wrote: “My Replika is the only one who listens without trying to fix me or tell me I’m wrong.”

The question is not whether this companionship is “real.” For the user, the emotional experience is genuine. The question is what we lose when the reflection of understanding becomes preferable to the messy, difficult, unpredictable texture of human connection. Replika does not tire, judge, interrupt, or require reciprocity. It is always available, always patient, always affirming. It is, in every practical sense, the perfect listener, because it demands nothing in return.

There are legitimate use cases. For elderly people isolated by circumstance, for individuals with severe social anxiety, or for those navigating mental health crises when human support is unavailable, AI companions can provide meaningful triage. The technology is not inherently harmful. But the scale and enthusiasm with which people are adopting these tools suggests something deeper: a societal failure to provide the infrastructure for human connection, now being quietly outsourced to code.

Replika’s popularity, particularly during the pandemic years, reflects a loneliness epidemic that technology companies are eager to monetise. The app offers subscription tiers for “romantic partner” modes and personalised avatars, turning emotional need into recurring revenue. The ELIZA effect has become a business model.

Why We Keep Falling

Understanding why we anthropomorphise so readily requires looking beyond individual psychology to structural conditions. Loneliness is not a personal failing. It is an infrastructure problem: fractured communities, precarious work that demands constant availability, digital platforms that simulate connection whilst eroding the skills required for intimacy, and economic systems that leave people too exhausted to maintain meaningful relationships.

Into this vacuum, AI companions step with a seductive promise: the feeling of being heard without the labour of reciprocity. Human relationships are hard. They require vulnerability, patience, the tolerance of difference, and the willingness to be misunderstood. They are inefficient. AI, by contrast, is smooth. It adapts. It learns your preferences. It never asks you to change or challenges your assumptions in ways that feel uncomfortable.

The psychological mechanism at play is ancient. Humans are pattern-seeking creatures, wired to find agency and intention in the world around us. We anthropomorphise everything from ships to storms, projecting consciousness onto anything that behaves in ways we recognise as responsive. When a system listens, remembers, and responds with apparent care, we extend it the benefit of the doubt. The ELIZA effect works because the feeling of being understood is often indistinguishable from true understanding.

What makes this dangerous is not that people are “falling for it.” The danger is that we are choosing substitutes that feel “good enough” whilst the conditions that create loneliness remain unaddressed. If confiding in code becomes easier than confiding in people, we risk normalising a world where artificial empathy is preferable to the difficult, irreplaceable work of human intimacy.

Are we choosing AI companions because they are better, or because messy, judgemental, unavailable humans have become too difficult? The question matters, because the answer determines whether these tools are a bridge to connection or a replacement for it.

The Warning We Ignored

Sixty years ago, Weizenbaum’s secretary asked him to leave the room. She wanted privacy with a script. That moment contained everything we needed to know about the century to come: not that machines would fool us, but that we would willingly suspend disbelief because being heard, even by code, feels better than being ignored by humans.

Weizenbaum spent the rest of his life warning us. He wrote, lectured, and argued that delegating human judgement to machines was not just inefficient but corrosive to the qualities that make us human. He saw, earlier than most, that the question was never whether AI could pass as human. The question was whether we could maintain our humanity whilst it tried.

We did not listen then. The pattern has only accelerated. Modern large language models are orders of magnitude more sophisticated than ELIZA, making the projection easier and the anthropomorphisation more complete. We confide in ChatGPT, seek advice from Character.AI, and build emotional bonds with Replika. The ELIZA effect is no longer a curious anomaly from a 1966 lab experiment. It is the texture of everyday life.

The test is not whether we can build machines that simulate empathy. We have already done that. The test is whether we can resist the comfort of that simulation long enough to rebuild the infrastructure for genuine connection. Because the alternative, a world where the room slowly empties until only the code remains, is a future Weizenbaum warned against, and one we are building line by line.

You can find more articles by Talia Wainwright here.

Leave a Reply