Introduction

Somewhere among my box files of HyperCard disks and yellowing ZX81 magazines, there lives a quietly unsettling thought: I have written more computer code than I have birthday cards, but I now watch artificial intelligence generate working Python scripts in less time than it takes to fumble a VHS into the recorder. For those immersed in retro tech, this is both familiar and faintly uncanny. The topic of Gen X and AI adaptation does not lend itself to glib confidence. It is, instead, a rich amalgam of curiosity, mistrust, pride, and the stubborn itch to poke behind the curtain, even when “the curtain” is: an algorithm with a name like a minor Doctor Who villain.

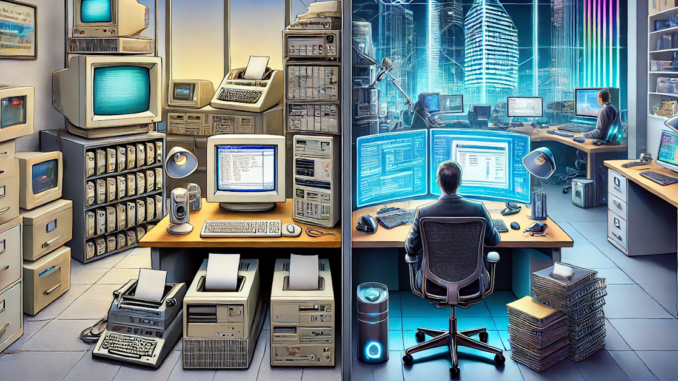

The early digital world never quite promised us flying cars or breakfast in pill form. It did, however, train us in continuous adaptation. We debugged BASIC, endured the failures of digital pets, and, most important of all, learned to question how and why any system worked or failed to. Now artificial intelligence stands before us. Unlike the pristine sci-fi dreams of yesterday, it is real, present, and being applied everywhere from chatbots to automatic sausage roll counters.

So what does Gen X and AI adaptation look like when you have the muscle memory of tape-loading errors and the wariness of someone who’s seen more “killer app” promises than you care to recall? That, I suspect, is where the story gets interesting.

Learning to Mistrust the Machine: A Gen X Crash Course

Academic research shows early digital adopters develop a sceptical relationship with automation. Gen X, for better or worse, came of age amid systems that were always on the verge of letting you down: Teletext scores interrupting a penalty shoot-out, floppy disks corrupted by an errant magnet, and the Windows 95 “It is now safe to turn off your computer” screen which, frankly, lied more often than it told the truth.

We learned resourcefulness. If your word processor crashed, you developed an obsessive habit of hitting Ctrl+S. If Excel suggested that macros would “revolutionise your workflow,” you saved your work and kept the manual handy once it inevitably mangled your formatting. The arrival of AI presents much the same dynamic, only now the manual is an improbable pile of PDFs, and the glitches occasionally appear sentient, at least in their unreasonableness.

Gen X and AI adaptation, then, is not a story of techno-lust, but one of uneasy alliance. Many of us approach new AI tools with a mixture of professional curiosity and philosophical alarm. Generative art, we notice, can conjure images of 1980s home computers that never existed, buzzing with simulated CRT glow. Yet it cannot tell you what it smelled like when an Amiga’s power supply decided it could no longer endure a second season of Knightmare.

Tools, Tactics, and Tension: Modern Implications of Gen X and AI Adaptation

Today’s artificial intelligence excels at the kind of repetitive, rules-based work that once fell to the most junior employee or, in my case, to the sleep-deprived university student with the least effective essay-writing hangover strategy. Machine learning sorts emails, schedules interviews, flags questionable expenses, and offers writing prompts that try, often in vain, to match my own comfort with subordinate clauses.

There is something almost touching about the earnest productivity of these systems. I have used AI to transcribe interviews, clean up old demoscene photos, and filter spam with greater success than any human gatekeeper (though I remain haunted by the time it confused Alastair Reynolds with a promotional message for a garden centre). Gen Xers, having witnessed the collapse of tech utopias from dot-com to digital government, rarely confuse efficiency with wisdom.

There is also, however, a deeper discomfort. Trust in AI is earned, not given. We know from decades of British computer history that “smart” features, be they predictive text, spellcheck, or Windows Update on a Friday afternoon, are as likely to upend your plans as improve them. Today’s bureaucratic enthusiasm for anything labelled “AI” invites the same rolling eyes once reserved for the paperless office, or indeed, for Clippy.

What stands out is how Gen X embraces tactical, not total, adaptation. We use AI to accelerate the drudge work. We resist its encroachment on interpretation, context, or the messy, joyful business of making sense when the code or story breaks down. It is not for lack of technical skill, but an inherited caution: Who benefits, who decides, and what gets lost in the march to automate?

Questioning Progress: Culture, Ethics, and the Human Factor

This reluctance is not nostalgia; it is political, ethical, and fiercely contemporary. Gen X and AI adaptation raises the question not just of how to survive technological upheaval, but how to shape it for human ends. It was Donna Haraway who wrote about the pleasures and terrors of boundary crossing in her cyborg manifesto. Today, most AI is trained on a culture that neither asked permission nor listened carefully to divergent voices. The risk is that automation amplifies not only efficiency but every systemic bias and blind spot from the last fifty years.

Academic research shows that far from eliminating jobs, AI alters the conditions of work and often redistributes drudgery downward. Algorithmic management, long trialled in “gig economy” sectors, now infiltrates traditional workplaces. AI might unburden us from scheduling, but it also watches over keystrokes and priorities with the serene indifference of a Tamagotchi on low batteries.

Gen X was never promised a future of leisure. The dream was always muddier but more interesting. We built mix tapes by hand, not because it was the only option but because it revealed things about taste, patience, and longing. Algorithmic playlists, efficient as they are, rarely transmit the tremor of embarrassment attached to that one dodgy Lisa Stansfield track at the end of a C90.

Culturally, every act of adaptation remains an act of meaning-making. Whether we automate the routine or resist the automated judgement of a performance review form, we insist, sometimes quietly, sometimes with wit, that the most important work cannot be outsourced.

Conclusion

Adaptation, for Gen X, has always meant more than mastering new devices. It is a process of selective, suspicious engagement, learning the system just well enough to bend it to your purposes while holding fast to the messy, beautiful bits that do not compute.

Gen X and AI adaptation can teach us much about how to live with technology without surrendering to it. We are the last generation to have used both cassette players and quantum-resistant cryptography in the course of a single week. I suspect it is our job to keep asking the daft, vital questions: should we automate this, or must it remain delightfully, heartbreakingly human?

If you’re weighing up whether to let an algorithm pick your next book or curate your old ZX artwork, I offer only this: proceed with curiosity, caution, and your favourite subordinate clause. For further reflections on digital ethics and retro invention, my archive is open at Talia’s articles. Stay curious, and, if at all possible, keep the mixtapes analogue.

Leave a Reply