Introduction

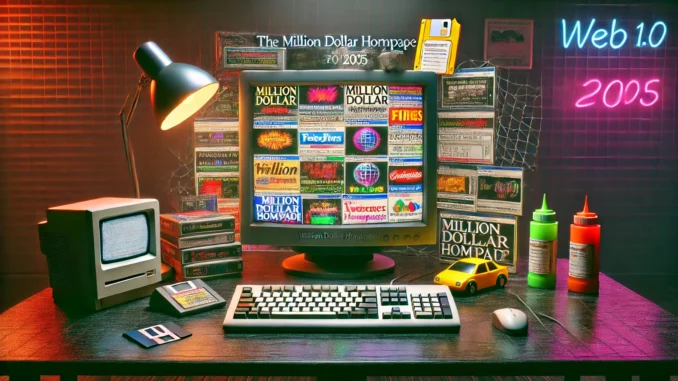

One wet November evening in 2005, I found myself hunched over my ancient ThinkPad in my Manchester flat. I was scrolling through a local IRC channel when the talk turned to something bizarre: a lad called Alex Tew, a uni student from Wiltshire, had thrown up a simple web page selling 1000 by 1000 pixels of screen space, a dollar a pop. At first, I scoffed. Most of us in my crowd still thought “influencer” sounded like a dodgy PowerPoint virus. Yet there was something raw and irresistible about The Million Dollar Homepage. It wasn’t slick or polished. It was daft, cheeky, and in its own strange way, deeply human.

You could almost smell the burnt motherboard dust and budget instant coffee in that idea. This was the web as we remembered it: a little experimental, a bit rough round the edges, bustling with forum banter and old-school banner ads. The Million Dollar Homepage wasn’t just a one-off digital stunt; it was a mirror to our own desire to be seen, even if only in a tiny, 10×10 pixel patch among a thousand strangers. As someone who has spent the last three decades digging up forgotten net relics, I see this site not as a joke, but as a time capsule for how community, novelty, and a sense of urgency once drove the whole blooming internet.

The Real Goldrush: Why The Million Dollar Homepage Worked

Forum archives from 2005 show lively debates across the UK, from Slashdot threads to local pub-based BBS spin-offs. Most people didn’t know what to make of it. Was it genius or grift? Was it art, business, or online vandalism? On one Manchester tech board, a user joked, “You’d be better off flogging pixels than wincing at dot-com shares.” There’s the unvarnished spirit of the early web: skepticism, but a readiness to join in if the thing looks even half a lark.

At the heart of The Million Dollar Homepage was scarcity. That was the draw: scarcity, then curiosity, then a fever that spread across blogs and forums at a speed that felt thrillingly unpredictable at the time. The digital patchwork that grew was gloriously messy, a jumble of startups, casinos, joke sites, marriage proposals, and even a local fish and chip shop from Lytham St Annes, whose bit of advertising remains frozen on the page like parsley in aspic.

Crucially, Alex Tew’s idea worked because it wasn’t really about advertising or technical wow; it was about belonging. Every pixel bought was a tiny act of “I was here,” like tagging your initials on the wall at the Hacienda. Only you didn’t need a marker pen or a balaclava, just a PayPal account and a sense of mischief.

The Million Dollar Homepage, NFTs, and the New Digital Scarcity

It’s strange to look back knowing how far the web has come. These days, digital scarcity usually means NFTs or blockchain, technologies nobody on my old BBS would have believed outside a Gibson novel. Yet, in many ways, The Million Dollar Homepage was a prototype for that whole idea. People were paying not for content, but for the right to exist, visibly, in digital stone.

Internet Archive captures show how the site’s original links are now a patchwork of broken dreams. Many businesses are gone; some squares lead to 404 errors. But the page survives, a testament to how quickly the cultural web can shift. Digital preservation experts warn that without care, even viral sensations will end up lost, one broken link at a time. I keep returning to the lesson here: most digital glory is fleeting, but its impact shapes our behaviour for years.

The Million Dollar Homepage also proved that the web could make overnight celebrities out of ordinary people and turn a daft idea into a shared cultural event. Word of mouth, forum drama, blog mentions, these were our viral engines, not algorithms or corporate campaigns. Community leaders from that era confirm it was a badge of honour to have your forum’s logo somewhere on Tew’s grid, even if few could find it without zooming in.

In the DNA of Today’s Web: Novelty, Hype, and the Battle for Attention

Looking at the modern internet, the fingerprints of The Million Dollar Homepage are everywhere. Social networks trade in something similar to pixel scarcity: the infinite scroll, the limited username, the frenzied search for viral stardom. Kickstarter, Patreon, and digitally scarce art projects all thrive on the promise of exclusivity and early access, more echo of Alex Tew’s original gimmick than you might think.

My own experience with running digital heritage projects reveals the biggest shared urge: to be seen and remembered, even in a sea of white noise. The messy mosaic of the Million Dollar Homepage did more than sell ad space; it sold the promise that something fleeting online could last, that for a few quid, anyone could carve their initials into a digital tree.

But what else did we learn? The page’s battered links are a warning. 21st century web projects vanish quickly. Whether it’s a digital art collective in Salford or a meme archive from Stockport, survival takes vigour, luck, and, above all, community will.

British Wit on a Global Stage: Regional Footprints in the Pixel Patch

I’ve spent hours poring over those original pixels, tracking down the northern and British contributions for posterity. One of my favourite finds was an old computer repair service in Middleton that once boasted, “We fix what your dad can’t.” The pride, local humour, and entrepreneurial risk of small UK businesses is hidden in those tiny squares, jostling for attention beside American casinos and Japanese tech gimmicks.

Early adopter interviews reveal that several British forums ran mini-campaigns to scrape together enough for a 10×10 patch, not for site traffic but bragging rights and a bit of a laugh. They’re the unsung characters of the internet, the same people who built out our usenet archives and filled GeoCities with neighbourhood charm before the big brands moved in.

What’s the Legacy? Reflection and Renewal

Nearly two decades later, The Million Dollar Homepage stands as a curious crossroads in internet culture. It reminds us how quickly a wild, playful idea can become both a phenomenon and a cautionary tale. It was the DIY web in microcosm: messy, funny, easy to lose, and easy to love.

If you’ve still got a screenshot or a memory of your patch on that chaotic page, hold onto it, or better yet, let me know. And if you’re tempted to start your own digital patchwork, whether it’s through a Mastodon instance, IndieWeb blog, or a zine site made on a Raspberry Pi in your box room, this is your sign to go for it.

Let’s keep our web weird, wild, and rooted in the everyday stories that built it. If you fancy exploring more of these forgotten digital landmarks or want a community that understands why they matter, you’ll find a warm welcome on my archive at Netscape Nation. So pour a brew, dust off the old forum logins if you’ve got them, and join me in keeping these quirky corners alive. Digital history, after all, is made of people, not pixels.

Leave a Reply