When your earliest memories involve the tang of burnt solder and a mess of ribbon cables instead of cartoons, you grow up with a different sense of heritage. I never pretended I’d been there for the kitchen-table kit revolution, but my education began in its aftermath, knees under my family’s dining table, tracing the tracks of someone else’s original assembly. Some kids inherited stamp collections; mine was a battered Amstrad CPC 464, an ancient soldering iron, and, if I was lucky, a box of half-intact back issues of Practical Electronics. My real obsession started later, elbow-deep in dead boards, reverse-engineering what previous generations hand-built out of necessity. This wasn’t nostalgia for nostalgia’s sake. The real story of the self-built computer isn’t a sepia-toned reel of old coders soldering away; it’s about agency, community, and the urge to shape your own tools, even as that urge mutates through decades of British tech culture.

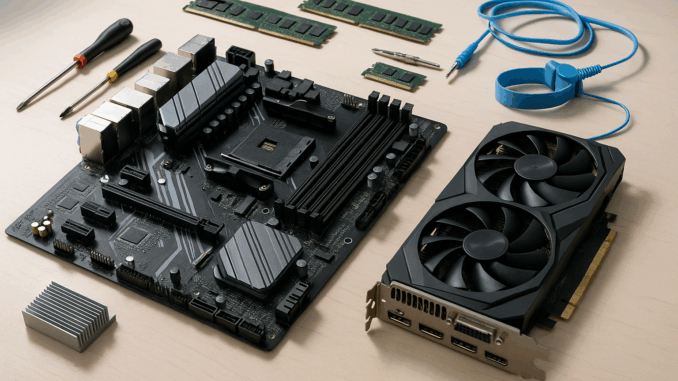

What have we lost, and what are we rediscovering, as the journey takes us from build-it-yourself kits to one-click prebuilt gaming PCs and then rapidly back to maker benches crammed with Pis, Arduinos and things with more GPIO pins than sense? To answer that, I need to start where I always do: with what we can touch, fix, and remake.

1970s: The Mail-Order Self-Built Computer Revolution

Long before my own encounters with oxidised edge connectors, the British self-built computer was a postal event. The old hands are still out there on forums, swapping tales of nervy afternoons surrounded by poly bags of components, hoping against hope that their first homebrew ZX80 wouldn’t let the magic white smoke escape. I can cite dozens of period threads and issue scans: the original Science of Cambridge MK14 manual is brutally blunt about the builder’s burden (“The builder should be familiar with basic soldering techniques”). The Altair 8800 wasn’t quite local, but even across the pond, “kit” always meant “you’ll probably have to debug it yourself”.

The real British badge was the Sinclair ZX80 or the MK14. You would order from the back page of an electronics mag, wait impatient weeks for the kit, then spend evenings that blurred into weekends hunched over a soldering iron. This was more than a technical process: it was a family event, or at least a shared ritual. In the wilds of early user groups, before even the Micro Mart pop-up stands became a thing, the sense of camaraderie was baked in. If your build blinked a single LED, it was a triumph for the entire club.

The difference then was necessity. Soldering joints was not hobbyist flair; it was the only way most people could afford a computer at home. Manuals didn’t walk you through the process gently; they assumed a level of hands-on literacy that seems almost alien today. Old issues of Practical Wireless or Your Computer list the expected faults alongside the parts manifest: cold joints, dodgy 555s, a maths co-proc that was always one pin away from uncooperative. For those who made it through, the self-built computer wasn’t just a device but the proof, smoking fingertips and all, that technology could be made truly yours. You had to earn it.

1980s: Hello, Polished Plastic (and Goodbye, Solder)

By the time Alan Sugar’s Amstrad CPC464 and Clive Sinclair’s ZX Spectrum were scoring prime shelf space at Boots, British computing was changing shape. Those machines arrived fully built, resplendent in their factory-moulded cases, ready to go from box to BASIC with only the mild perils of a wobbly tape deck to slow you down. The BBC Micro, of Micro Live and Computer Literacy Project fame, became a schoolyard fixture not because anyone was soldering them in science class, but because BBC’s Television Centre promised a future with keys and code, not leads and flux.

The self-built computer was going out of fashion, and with it, a certain kind of cultural grit. But in its place, we saw new communities nucleate around different forms of agency; DIY shifted to hacking together peripherals or eking out a bit of extra RAM instead. I’ve seen this reflected again and again in both oral history interviews and repair logs: people traded soldering for the thrill of finding poke codes, joined coding clubs, and gleefully chased after elusive sprite glitches on 80s CRTs. If you had a Spectrum, you were more likely to mod your tape recorder than mess about inside the ULA chip itself.

There’s a reason the Your Sinclair review archive is full of discussions about expansions, not kit builds. The magic was no less powerful, just less electron by electron. The few who still fancied themselves home engineers gravitated to magazines like Practical Electronics, where you could build a RAM pack or joystick interface and gain schoolyard legend status. The kit spirit simmered under the surface, refracting through joystick interfaces and parallel printer boards.

1990s: Rise of the Bedroom Self-Built Computer Builder

Just when it all seemed settled, and each home computer had its own manufactured personality, the market atomised. Enter the beige tidal wave: cheap PC clones sold in bits and bobs at fairs or the local computer market. There’s a certain thrill in digging through those old issues of Computer Shopper, the classifieds thick with “AT chassis, £29.99” or “386 motherboard, tested, £40 cash”. You weren’t soldering every connection any more – thankfully for most of us – but you were back assembling, slotting cards, cursing soft IDE cables and misbehaving jumpers until the small hours.

I built my first PC from parts bought at what is now a chain fitness club but in those days was a draughty function hall filled with trestle tables groaning under OEM leftovers. There was a genuine sense of pride in managing to get a Sound Blaster to coexist with a graphics card, and that achievement didn’t require a soldering iron, only brute stubbornness and the patience to parse DOS config.sys files line by line.

These years gave us the “bedroom builder”: kids and twenty-somethings alike learning hardware the hard way, plugged into BBSs and local user groups. Unlike the 1970s, the driver was no longer necessity. Now you built because you could get more power for less cash, or just because you wanted a PC that could run Doom and Microsoft Encarta side by side. Forums like Usenet’s comp.sys.ibm.pc.clones are awash even now with old war stories: “The manual for the FIC 486 board warned about ISA slot clashes, but I thought I knew better…”

This is where I cut my teeth, not first-hand, but as an interloper, resurrecting and repairing the leftovers, learning from the logs and tales left behind.

2000s, Now: Decline, Then Maker Revival

With laptops, iMacs, and “sealed for your inconvenience” all-in-ones taking over the market in the 2000s, building your own system began to look like a specialist hobby, and sometimes a pretty showy one at that. RGB fans and clear cases might get the Instagram limelight now, but practical self-builds became the preserve of a shrinking club of enthusiasts and bargain hunters. Spare parts weren’t stacked in the local Classifieds section; they were scattered on eBay or hidden in the dreaded “Untested, for parts only” listings.

But then, everything old became new again, only in a slyer, smaller form. Enter the Raspberry Pi, not so much a revolution as a throwback with better documentation and an optional GPIO breakout board. Arduino and microcontroller kits made building accessible again, only now you didn’t need an entire Maplin wall to start – just a shoebox-sized kit and an internet connection. Today, my workspace, now in Bucks, though it sometimes feels like a Brighton repair bench in spirit, is filled with microcontroller projects and Pi-based hacks. It’s gloriously reminiscent of the 1970s in spirit, if not in form factor. Maker fairs and Hackspaces are the new church halls; Discord and YouTube have replaced local user group meetings but kept the same sense of camaraderie alive.

I see kids soldering together weather stations or retrogaming Pi cases, chasing different sparks of joy than our parents did. The learning curve isn’t measured so much in soldering scars as in error messages and eleventh-hour eureka moments, but the result is the same: a real sense of agency and ownership. Forums today might look different, but that old instinct to tinker, share, complain and collaborate is very much intact. For anyone who ever waited for a Ceefax page to load, the rhythm of anticipation and discovery hasn’t changed; just the medium.

Reflections: What’s Lost, and What Survives in the Self-Built Computer Era?

So, is something crucial lost as self-built computers become less about kit form and more about modularity, emulation or scripting? In a sense, yes: the visceral sense of physical creation has been smoothed over by plug-and-play and one-click OS flashes. I will always envy those with first-hand memories of their family’s first boot from a breadboarded Sinclair kit; it’s a feeling I only access second-hand, through restoration and the stories preserved in fading printouts and frayed manuals.

But the impulse, that urge to make and remake, never vanished. If anything, it has evolved. The builder spirit has simply migrated. Where once we shared a pot of tea halfway through assembling a ZX80, we now crowdsource bug fixes on GitHub or share progress pics in Discord chats. We replace blown caps in aging power supplies not just to keep the LED lit, but as acts of preservation and homage.

If you value agency and creativity, keep building, whether you’re patching up a 1989 Amiga 500, giving fresh purpose to a Pi Zero or 3D printing enclosures for a homebrew MIDI controller. Because every era that lets the self-built computer thrive is another chance to prove, solder burns or otherwise, that our tech is still our own. And as right-to-repair and sustainability conversations heat up, today’s self-built computer culture is more than a hobby: it’s a statement of ownership and care.

If you enjoyed this dive, check out more features at https://netscapenation.co.uk/author/sophie/

Leave a Reply