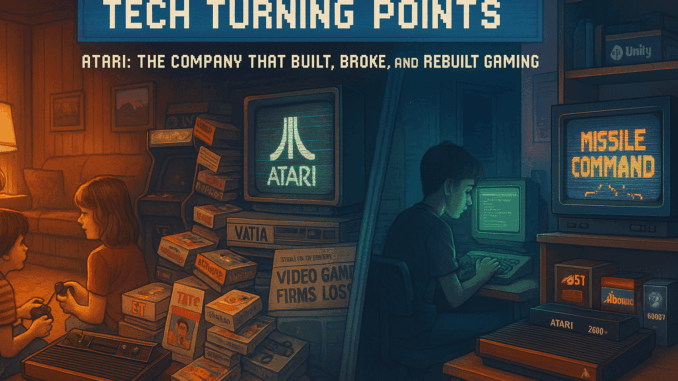

The contrast couldn’t have been starker. At the Consumer Electronics Show in January 1982, Atari commanded the largest booth on the floor, with queues snaking around demonstration pods as punters marvelled at the latest cartridges for America’s dominant gaming platform. Two years later, at CES 1984, many gaming companies had vanished entirely, their booth spaces filled by emerging personal computer manufacturers. In the span of 24 months, the video game industry had experienced the most dramatic collapse in modern entertainment history-and from its ashes would emerge a fundamentally transformed medium.

The Golden Throne: Atari’s Unprecedented Dominance

By 1982, Atari’s Video Computer System had achieved something remarkable in consumer electronics: genuine cultural ubiquity. The company controlled roughly 90% of the home console market, with the VCS/2600 installed in over 10 million American households. For British families discovering home gaming, Atari represented their first glimpse into interactive entertainment-Combat battles in Midlands sitting rooms, Adventure quests on rainy Yorkshire afternoons.

Yet even as Atari dominated, early competition was stirring in Britain. The BBC Micro had begun appearing in schools nationwide, whilst Acorn’s machines were establishing footholds in educational markets. These weren’t direct competitors to Atari’s entertainment focus, but they were quietly building the foundation for Britain’s distinctive computing culture.

The economics seemed unshakeable. Cartridge manufacturing costs averaged £3-4, whilst retail prices reached £25-30. Atari’s licensing model generated revenue from both hardware sales and third-party software royalties. The company’s 1981 revenue of $2 billion made it the fastest-growing corporation in American history at that point.

Yet beneath this success, fundamental problems were brewing. The very openness that had enabled Atari’s rapid growth-minimal quality control, easy market entry for developers-was creating conditions for spectacular failure.

Warning Signs: The Cracks Begin to Show

The first major warning emerged in 1982 with Atari’s adaptation of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. Following successful film tie-ins like Raiders of the Lost Ark and Superman, Atari expected their Spielberg collaboration to be the Christmas blockbuster that cemented their dominance. Instead, it became gaming’s most infamous cautionary tale.

Rushed into production to meet Christmas deadlines, the game epitomised everything wrong with the industry’s approach to development. Howard Scott Warshaw, the programmer, had just five weeks to create what Atari hoped would be their biggest seller. The numbers tell the story of corporate hubris: Atari manufactured 4 million cartridges for a game that ultimately sold only 1.5 million copies.

For retailers like Derek Matthews, who ran an independent game shop in Coventry, the warning signs were becoming impossible to ignore. “We’d order fifty copies of the latest Atari release and sell maybe twenty,” he later recalled. “The rest would sit there whilst customers started asking about these new computer things from Sinclair.” His experience wasn’t unique-across Britain, specialist retailers watched Atari inventory gather dust whilst Spectrum cassettes flew off the shelves.

Simultaneously, the market was experiencing unprecedented oversaturation. In 1982 alone, over 100 new cartridge titles launched for the VCS. Quality became secondary to quantity as developers rushed products to market. For British consumers browsing WHSmith’s expanding gaming sections-rows of cartridges in glossy packaging competing for attention under harsh fluorescent lighting-the sheer volume of choice created decision paralysis rather than excitement.

The Collapse: When Dominance Became Liability

The crash, when it came, was swift and merciless. Between 1983 and 1985, industry revenues plummeted from $3.2 billion to $100 million-a 97% decline that left the sector smaller than it had been in 1975. Atari, once worth $2 billion, was sold by Warner Communications for $240 million in 1984, split between Jack Tramiel’s new Atari Corporation and the arcade division.

The human cost was equally dramatic. Thousands of developers, retailers, and support staff lost their livelihoods as companies folded overnight. Independent game shops that had flourished during the boom found themselves stuck with worthless inventory. The cultural impact extended beyond economics-parents who had invested in expensive gaming systems felt betrayed, whilst children watched their favourite hobby seemingly disappear.

British retailers proved more resilient than their American counterparts, largely due to diversified inventory strategies. WHSmith’s combination of books, magazines, and stationery provided insulation that specialist game stores lacked. This diversification enabled faster pivots to home computers, with many stores simply replacing Atari cartridge displays with rows of Spectrum cassettes in cheap plastic trays-their photocopied inlays a stark contrast to the glossy packaging they replaced.

Britain’s Different Path: Opportunity from American Chaos

Whilst America mourned the death of console gaming, Britain was experiencing a renaissance of a different sort. The crash had created a vacuum that home computers were perfectly positioned to fill. The Sinclair ZX Spectrum, launched in 1982 at £125, offered superior graphics and programming flexibility compared to aging American consoles.

British gaming culture diverged dramatically from its American counterpart during this period. Where American consumers had become passive purchasers of cartridges, British users embraced the active culture of programming, copying, and modifying games. Bedroom programmers like Matthew Smith (Manic Miner) and the Oliver Twins (Dizzy) became household names, creating a uniquely British gaming identity.

The economics were fundamentally different too. Cassette-based distribution meant production costs of pence rather than pounds, enabling experimental gameplay and niche titles that would never have justified cartridge manufacturing. Computer & Video Games magazine reflected this shift, gradually moving from American import coverage to celebrating homegrown talent.

Lessons Learned: The Industry Rebuilds

When Nintendo launched the Nintendo Entertainment System in America in 1985, the company had studied Atari’s failures meticulously. Their solution was radical: complete platform control. Every game required Nintendo’s approval, with strict quality standards and production limits. The infamous “Nintendo Seal of Quality” became gaming’s equivalent of a safety certificate.

This gatekeeping model, born directly from the ashes of Atari’s collapse, established principles that persist today. Modern console certification processes, app store approval systems, and platform holder quality standards all trace their lineage to lessons learned from 1983’s chaos.

The crash also professionalised game development. The cowboy era of five-week development cycles and minimal testing gave way to structured project management, quality assurance processes, and market research. Publishers emerged as crucial intermediaries between developers and platform holders, providing the financial stability and market expertise that individual programmers lacked.

Figures like Jeff Minter, who survived the transition from the Atari era to home computers and beyond, embodied this new professionalism whilst maintaining creative independence. “The crash taught us that talent without discipline is worthless,” Minter reflected years later. “But discipline without creativity is equally dead.”

Modern Echoes: History’s Persistent Patterns

Today’s mobile gaming market faces remarkably similar challenges to those that destroyed Atari. App stores contain millions of titles, most of which disappear without trace. However, crucial differences have emerged from hard-learned lessons: algorithmic curation helps surface quality content, freemium models have changed economic pressures, and platform holders maintain stricter oversight than Atari ever attempted.

The economics of digital distribution have recreated the oversaturation problems of 1983, just with different technology. Yet modern discovery mechanisms-user reviews, recommendation algorithms, influencer coverage-provide market-driven quality filters that didn’t exist in the cartridge era.

Platform holders have learned to balance openness with control. Apple’s App Store approval process, whilst often criticised, prevents the complete quality collapse that characterised the early 1980s. Steam’s recommendation systems and user reviews create community-driven curation that protects consumers whilst enabling creative experimentation.

The crash also demonstrated how quickly technological dominance can evaporate. Atari’s 90% market share seemed unassailable in 1982, yet within two years the company was effectively finished as a major force. Today’s platform holders-Sony, Microsoft, Nintendo-understand that market position requires constant innovation and careful ecosystem management.

The Human Resilience Factor

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of the 1983 crash wasn’t the collapse itself, but the speed of recovery driven by human creativity and determination. Whilst corporate executives mourned lost profits, bedroom programmers, independent retailers, and passionate players kept the medium alive.

In Britain, this resilience took the form of user groups, programming clubs, and magazine communities that sustained gaming culture through its darkest period. Small software houses like Ultimate Play the Game and Imagine Software proved that innovation could flourish outside corporate structures. Independent retailers adapted by embracing home computers, creating the foundation for Britain’s distinctive gaming culture.

The crash taught the industry that sustainable growth requires more than technological capability-it demands respect for creators, consumers, and the medium itself. The companies that emerged from the wreckage understood that gaming wasn’t just another consumer electronics category, but a new form of art that deserved careful cultivation.

Creative Destruction in Action

The Great Video Game Crash of 1983 represents capitalism’s creative destruction working exactly as intended. The industry that emerged was more sustainable, more professional, and ultimately more innovative than what came before. Atari’s fall cleared space for Nintendo’s rise, enabled Britain’s home computer renaissance, and established quality standards that protected consumers from future market flooding.

The crash reminds us that technological turning points often involve destruction as much as creation. Sometimes an industry must nearly die to be reborn stronger. The gaming medium we enjoy today-with its careful platform curation, professional development standards, and global creative communities-exists because a previous generation learned hard lessons from Atari’s spectacular collapse.

In the end, the crash of 1983 wasn’t gaming’s death-it was its graduation from novelty to art form, from hobby to industry, from American curiosity to global phenomenon. The players, programmers, and shopkeepers who refused to let the medium die deserve recognition as the true heroes of this story.

Leave a Reply